There are less optimistic tones as well; the recurring refrain of a neoliberal power, of real estate ownership, and the capitalist necessity of profit versus often precarious conditions of creative work affecting other spheres of life. “A real problem in New York is rising real estate prices and living costs that make it more and more difficult to afford work and living space. That’s the main reason why many people decide to stay for a limited time only. And unfortunately, like in other parts of the world, fees for curators and artists are still under minimum wage which makes it difficult for everyone to survive without a second job,” says Sarah, and Bartek adds “Having a gallery is not always a solution for an artist either, since what sells is not always what is most interesting or really challenging. Artists, and curators, often have to compromise a lot, presenting safe & estheticized art to please the eye and sensibilities of market forces: patrons, collectors, etc. Things like social security and health insurance are a huge issue for creatives too, as is political correctness.” Similar thoughts are shared by Abner Preis. “The biggest problem in Amsterdam, of course, is the idea of real estate. Housing and studios are incredibly difficult to find; in that kind of situation it is hard to build groups in the sense of collectives, to share things as a community. Another bad thing is the economic pressure of having galleries constantly geared towards what is financially profitable; it does not help artists, especially young artists, in finding their voice.” And Zorka Wollny wraps up these concerns succinctly. “Bad things about Berlin? Gentrification and investors. All the best things in Berlin are threatened by rapid neoliberalism. That is scary.”

Virilion speed accelerates. Again clichés.

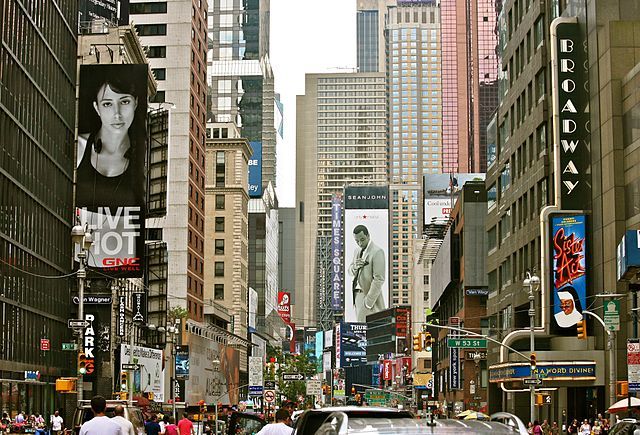

The ending phrase of a professional bio usually sounds the same: lives and works in the city. Sometimes there are two places indicating artistic commuting. But in real life conversations or small talk at art openings and parties, I have noticed that it is much more common these days to hear the question “Where are you based?” rather than “Where do you live?” A small but crucial difference. A base indicates readiness to move further, temporariness, a state of half-belonging and half-engagement. As if the nomadic fluidity of space to live was not related to various levels of engagement or relations, but rather to certain tasks, and at the same time suggesting that life itself was something happening at the margins of another project. Ironically enough, the very common need for personal ikea-zation of a new space in order to make it just a little bit cozier and individual illustrates this paradox quite well. The end result is the sameness of the all habitable spaces, marked by the little candles, wine glasses, fluffy blankets and comfy mattresses on which a head can dream of free time and real home.

Art, or more broadly speaking the culture field, is situated in a paradoxical axis of different expectations, awareness, imaginations and fluid borders of what constitutes work and free time, which altogether make this sphere extremely vulnerable in these times driven by ideals of productivity and profit.