I thought a lot about these questions, these histories of self-organization and artist-run spaces, my own history leading up to the conversation at Rogaland Kunstsenter. When I was initially invited by Studio 17, I was hesitant to accept the task of returning to this term, unpacking it’s complicated implications and its historical references. For recently, I have felt defeated by the inability to self-organize as a part of my own curatorial work. With the current political climate aside, self-organization has always had a bubbling problem of access and healthy longevity, even if a temporal parameter of time (“how long will we do this for?” or framing it as “project-based” work) is set from the beginning. The person or collectives proximity to funding opportunities from institutions, grants, ability to self-fund, to just name a few, as well as general burn-out rate.

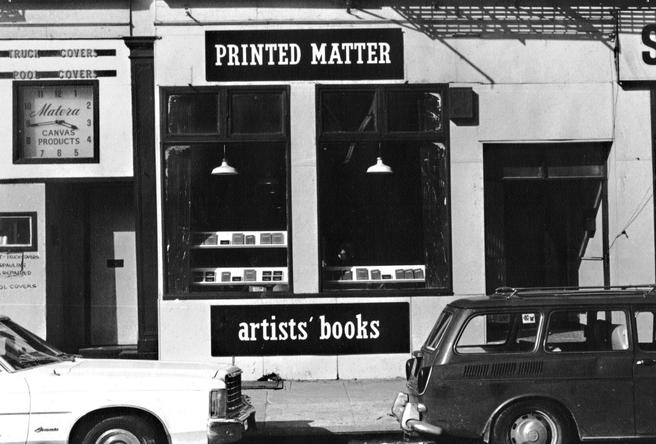

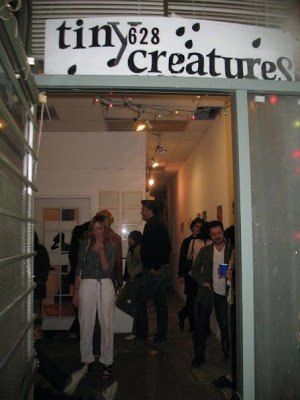

During our conversation at the Rogaland Kunstsenter, those of us around the table shared our experiences working for institutions and starting our own spaces or platforms, opening up a space that evening to share our best practices. We reflected on how to delegate work amongst a group, the problem of archiving a self-run space when the question of external historicizing (like what Kraus did for Tiny Creatures) was out of the question. I remember discussing how we find ways to communicate in our own individual projects, especially when communication flows in and out of personal, domestic space to a shared community. We were not there to define any singular truth, right or wrong way of working, but to hear each other out and provide a sort of support system for each other.

As one can imagine, the conversation wove in and out of our personal experiences and perspectives on this topic of self-organization to the Tiny Creatures text we discussed during the evening, occasionally anchoring our thoughts back into Chris Kraus’s words. What can be gleaned from our collective reading of Tiny Creatures, and our own stories, is that physical spaces are temporal. Much like we change with time, spaces change, too. New ideas and new people share all that they can to build a space in order to make room for others, ideas, and projects, and with this, the space fluxes, too. Internal and external variables, like grant funding and personal investment to the initiative, get real or fade away. Does this mean that there is, or will be, more of a turn to self-organization online? Not necessarily. It is my hope that people will always feel a need to share space with one another, and make room for new ideas to go against, or in friction to, the cultural and societal norm. We need it now more than ever.