I do see all the ways in which we romanticize craft. And but still it’s true that holding a well-made bowl feels some sort of balm. Making it, I would imagine, might also be a balm, and writing certainly is — the bringing out, the finding out the form. The disappearing into it, so that it can be made to disappear into the world.

Léonie: It’s probably one of the first things human beings figured out how to do: make a bowl, put something in it. So it goes back a zillion years and it’s constantly changing. You can be devoted to a craft, to a history, and what’s passed down in the discipline is fundamental, but at the same time people innovate, because without it a craft tradition would die.

Kathleen: Everything that’s ever been invented was invented by people who didn’t know how to do it and built on previous knowledge.

Anne: That’s the deep base of craft, that we are a species, one of a very few, that makes tools.

Almost everyone I spoke to for this essay invoked a spiritual dimension in their relationship to objects, and most did so after prefacing, “Not to sound too hokey/mystical/woo-woo…” This includes the instrument and furniture maker, musician, and sculptor Sung Kim, whose studio, Hare & Arrow Arts, I visited in an industrial section of Richmond, California, an hour’s bus ride from my home in Oakland. I was late for our end-of-day interview and he’d been at work since the early morning, but it didn’t seem to matter; his eyes were trained on the lathe he was operating, an everyday act of perfect attention.

Discussing his work, Sung evinced both the professional’s easy disinterest in preciousness and the inventor’s fervent, willed naïveté. He described “almost a fever” sometimes when he begins making something, even foregoing sleep as he seeks a connection with his creation. This, he said, was especially true when it came to his instruments (which, like much of the music he makes, are improvised): “You’re creating a voice for yourself that you don’t have, and then you’re learning how to speak with that voice. There’s nothing more intimate.”

Sung laughingly acknowledged that “the whole idea of shamanism and an object really does come to mind.” I thought of Slivka, whose forty-five-year-old essay invokes the shaman with neither embarrassment nor apology:

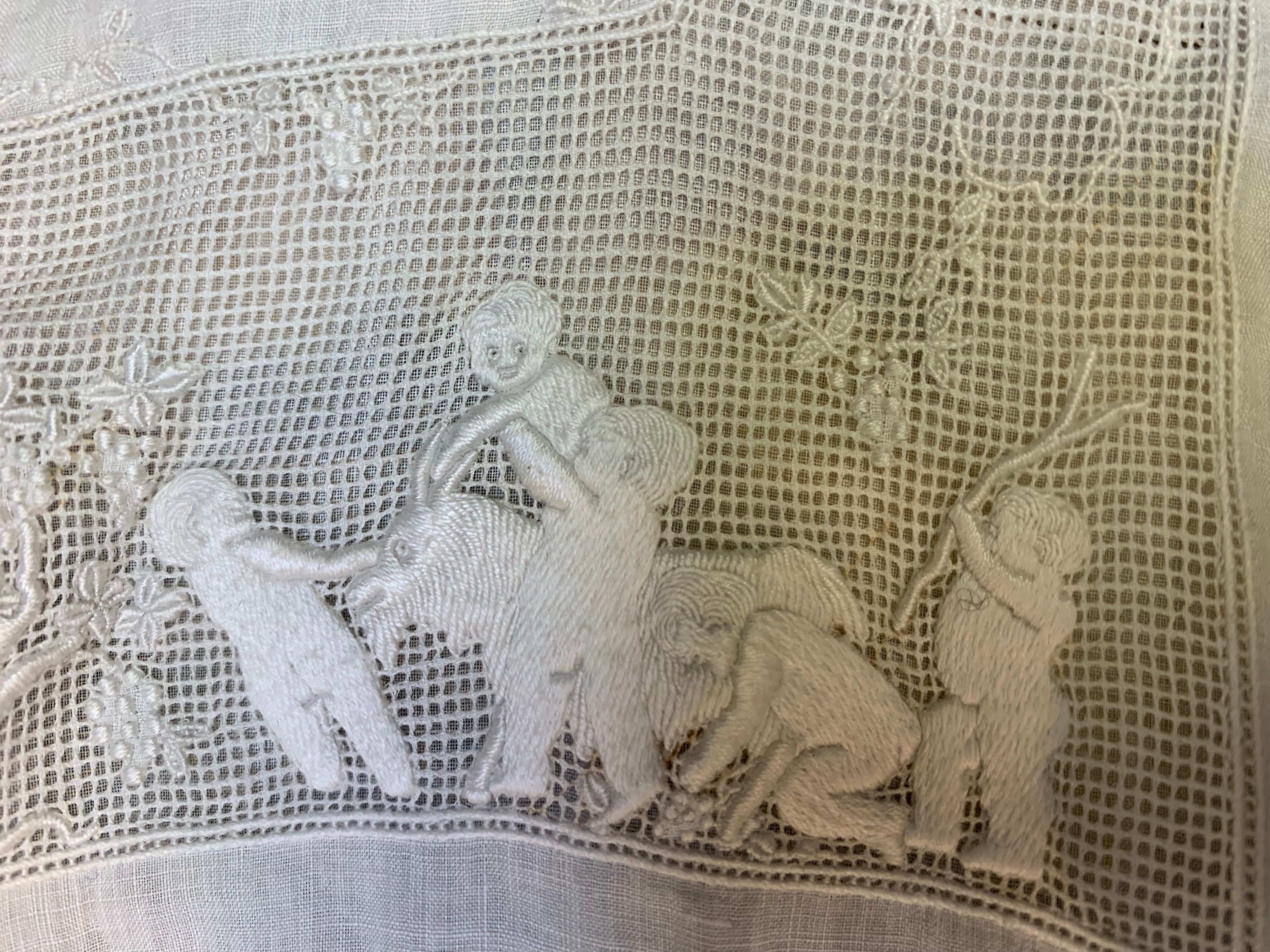

"The shaman invests the dream and the myth with magic, thereby keeping it safe for the imagination, for the life of the mind and the spirit, to make all things alive, to enter the mystery of the phenomena, to receive beauty, to see all sides of human nature including the evil, to find the hidden self. We confront the object and it reminds us of something, something old, something not yet known."

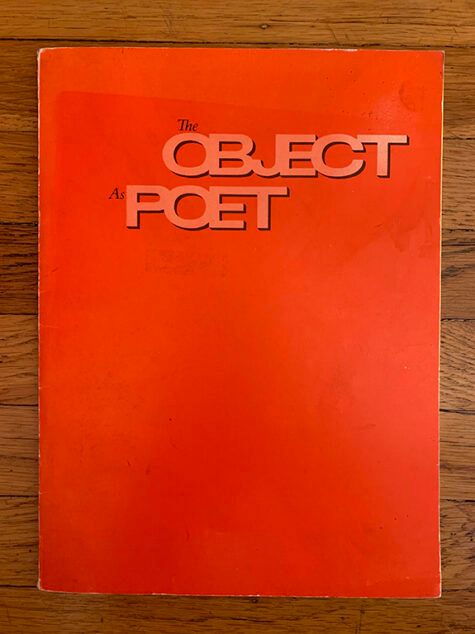

Dizzyingly romantic. But necessarily wrong? I can’t quite metabolize Slivka’s words, which conjure editor Maria Elena Buszek’s introduction to Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, in which she offers as problematic poles the craft world’s romance of materials and the art world’s “romance with the conceptual.”

When I had earlier asked my mother how she thought of something like Duchamp’s Fountain, she unhesitatingly included his art within craft. “It’s what you do with it, and this was an example of his craft.” She didn’t find the boundaries relevant. “You could say Isadora Duncan wasn’t much of a dancer by that definition. She didn’t do pirouettes, just whirled around.” Hoisted with my own (former dance critic’s) petard.