Hollows are Heroes

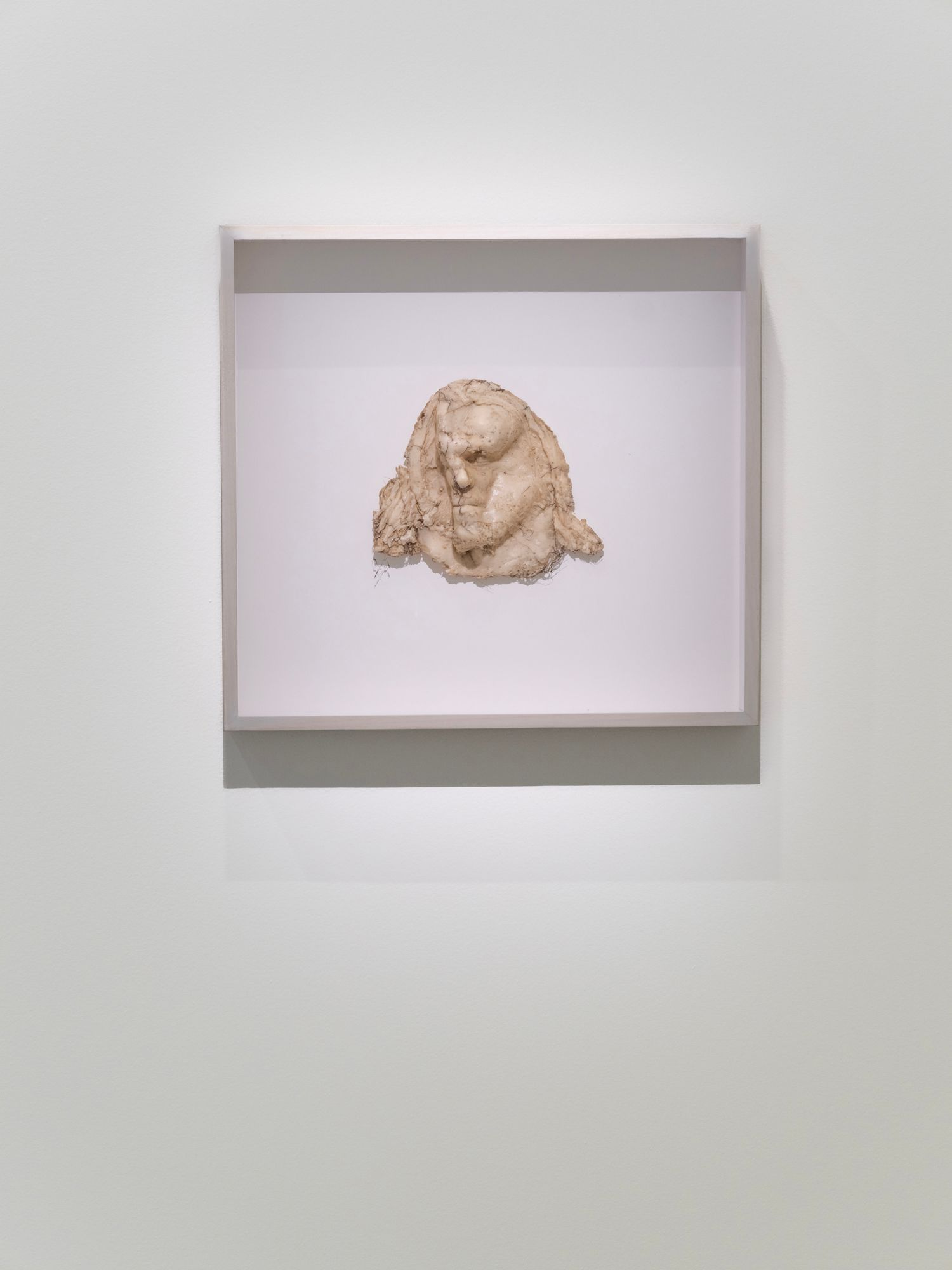

The exhibition The Plastic Body at Stavanger Art Museum presents Polish art from the period 1960 to 1989. As the exhibition title suggests, the body is the main theme in several of the works, and in line with the era in which they were made, synthetic materials are often used – an innovation within art materials at the time. The ten artists presented in The Plastic Body - which mainly exhibited sculpture – were all women, and their works serve as witnesses to a period in Polish art that many west of the Iron Curtain knew (and know) little about. Their works are voluminous, bending and buckling. And as an unpremeditated thematic twist that appears in hindsight, most of these works embody a form of hollow: a dip, a fold, a dent, a crack. A negative space.

This text is about the hollows. Those found in ourselves, in works of art, in concepts and in Venn diagrams (you know, the ones made up of two or more circles, more or less overlapping with each other).

In the science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” from 1988 she suggests that (pre)history isn’t really about spears and mammoths, but about containers to keep things in. The reason why we remember the spears is that a mammoth hunt makes a better story and is easier to paint on the cave wall. As Le Guin puts it, who wants to hear about how “I wrestled a wild-oat seed from its husk”. But apart from the things that enthralled our forefathers and foremothers round the fire, the real hero of history is “a thing that can contain something other than itself”: a container, a bottle, a box, basket, a purse. A hollow.

The hollows are the heroes of the essay you are now reading. They are transformative spaces that create the ground for imagination and ideas. In The Plastic Body these hollows are full of metamorphic potential – at times hopeful, often ill-aboding. We shall start with the latter.