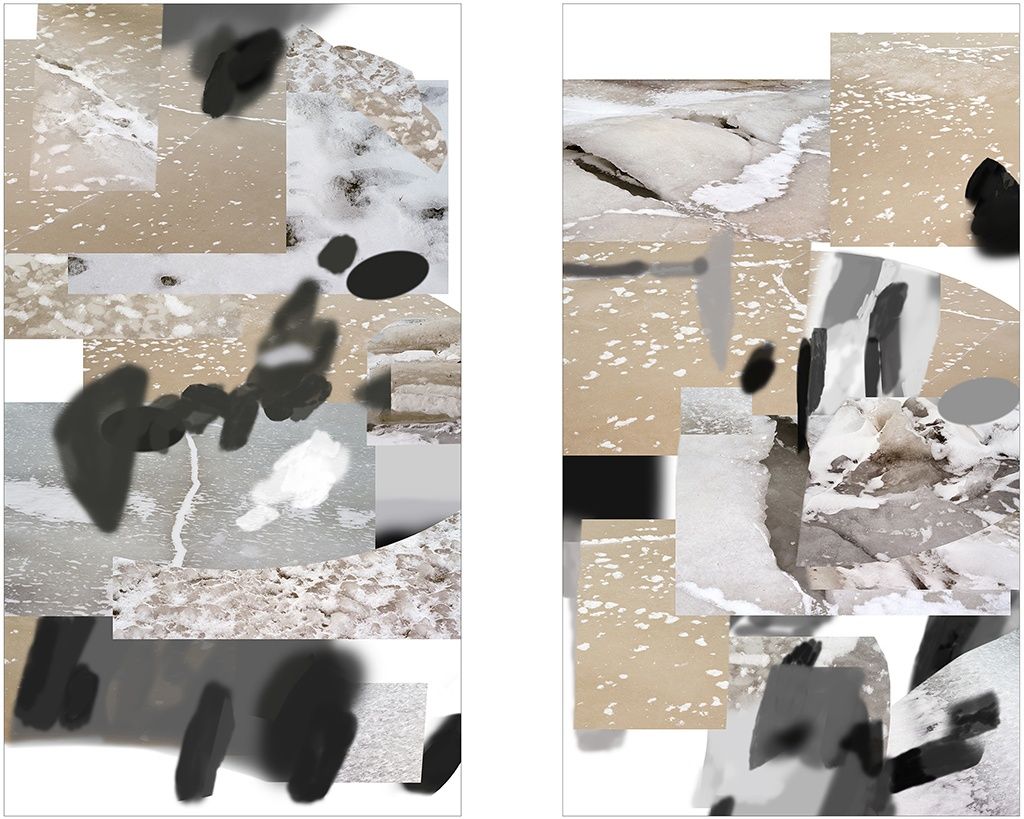

Leah Beeferman, Coast forms, 2017. Digital video and animation, no sound.

Some years ago, I first saw a map of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation, collected by NASA and the European Space Agency. I was equally drawn to the image itself — presented as an elliptical, pseudo-cylindrical map projection (also known as a Mollweide, elliptical, or homolographic map projection) — as I was to the fact that this colorful map somehow represented the electromagnetic radiation left over from the Big Bang; the average temperature of the universe (2.7260±0.0013 K, or -270.424ºC); and the universe itself, in its entirety, as an abstract image: one that suggests and represents everything, including and beyond us, in space and time. The ellipse itself is expansive: a form in two-dimensions that allows for thinking far beyond two dimensions.

When transferring information from the “real world” into an image, what one can ask of photography, or of abstraction? In nature, basic properties of matter (density, form, structure, color) emerge via complex geological, chemical, and biological systems, each guided by the interactions of subatomic particles. Some of these processes are observable, reflecting light in the visible spectrum back to our eyes or lenses; others are visible only to more specialized measuring tools, or to certain animals, which can see beyond those familiar wavelengths. The rest exists, to us anyway, perhaps only on a textual or numerical layer interwoven within: a layer expressed primarily in the languages of science or mathematics (that structured abstraction), visualizable, or perhaps not. Or it exists in the realm of lived or observational experience, where these layers of the visible, the textual, and the imagined are compressed into one complicated block, viewed, I suppose, only from within.

Artists are often asked to imagine new futures, but maybe we first need to re-imagine the present: to consider how we see and what we can’t see, in order to build a stronger foundation of looking, more attuned to the world itself, and, in turn, to our images of it. So I think about Eliot Porter, 1987: “As I became interested in photography in the realm of nature, I began to appreciate the complexity of the relationships that drew my attention.” And about Rebecca Solnit, writing about Porter in Every Corner is Alive, 2003: “Some of Porter’s flat-to-the-picture-plane images bring to mind [abstract expressionist] painting and even may have been influenced by it. Abstract expressionism famously emphasized the formal process of painting itself, or what in Jackson Pollock’s work was sometimes called ‘all-overness.’ Porter’s photographs exhibit a similar compositional approach, as well as a passion for process in ecological, rather than purely aesthetic, terms.” And about Luigi Ghirri, in Atlas, 1973: “Photography, with its power to constantly vary our relationship with reality, shifts the terms of the question, evoking an ‘illusory’ form of naturalness. In this case, reality and its conventional representation seem to coincide, and there’s a shift from the question of its meaning to that of its imagining. And so the journey lies within the image, within the book.”