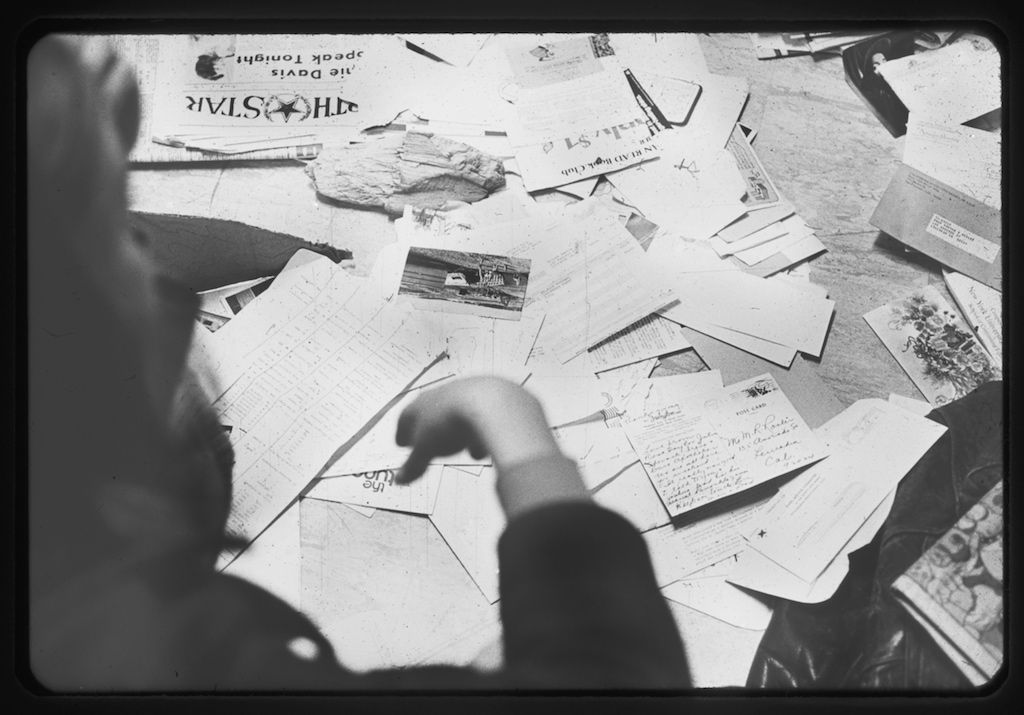

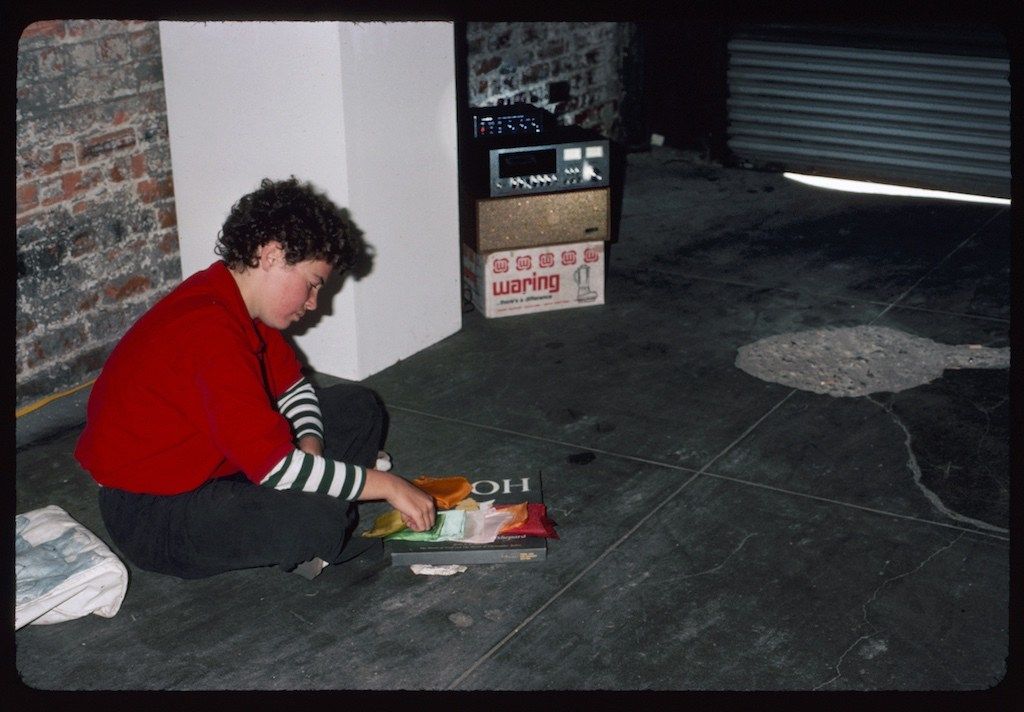

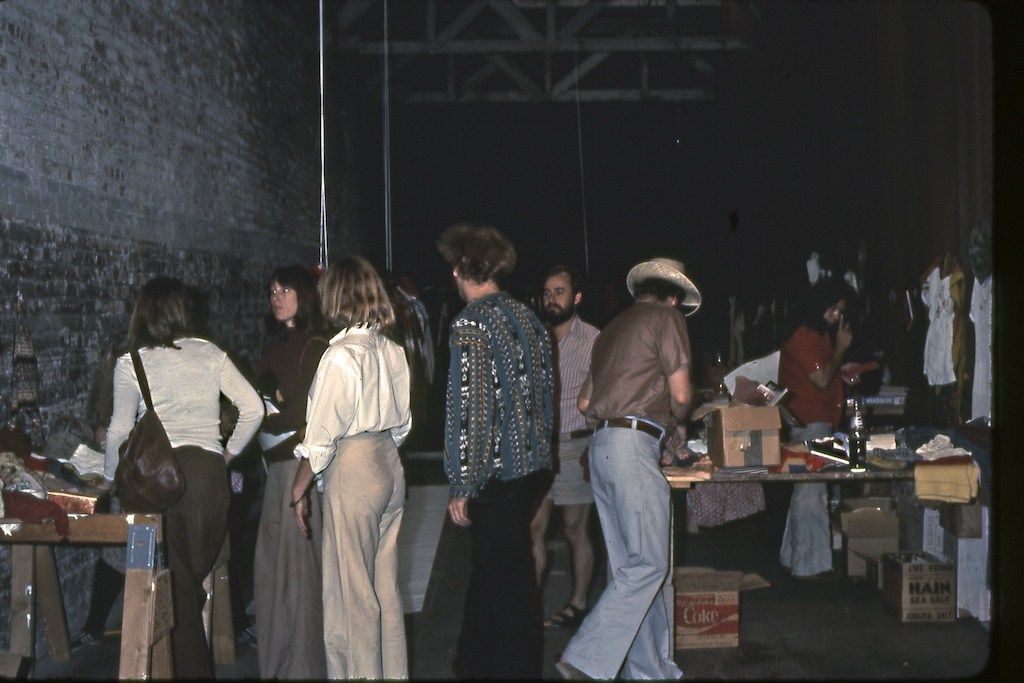

When I was a teenager in North Carolina, I would wake up early on Saturdays to go to garage sales with my parents. My father, who grew up in North Africa and learned to haggle very young, would make coffee while my mother, the daughter of an American traveling salesman, meticulously read through the classified section of the newspaper listing all the garage sales in the Greensboro/High Point/Winston-Salem area. We had an enormous, fold-out, street-by-street map of Guilford County and a color-coded highlighter system with which to plot an itinerary for the hours we would spend looking for The (illusive) Garage Sale Find.

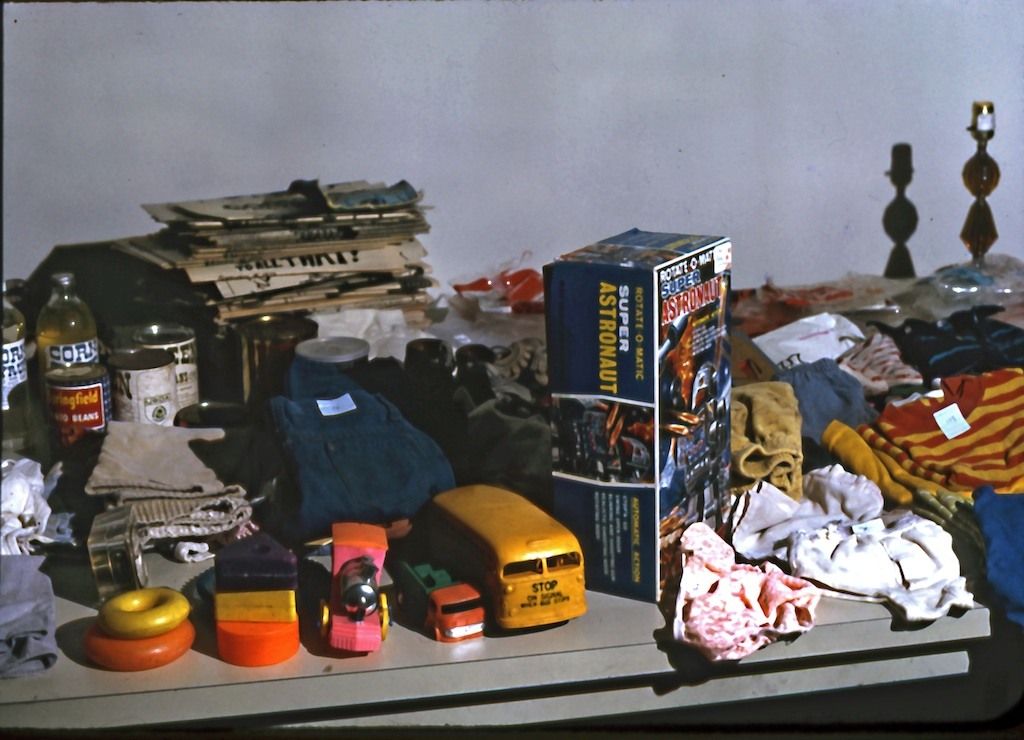

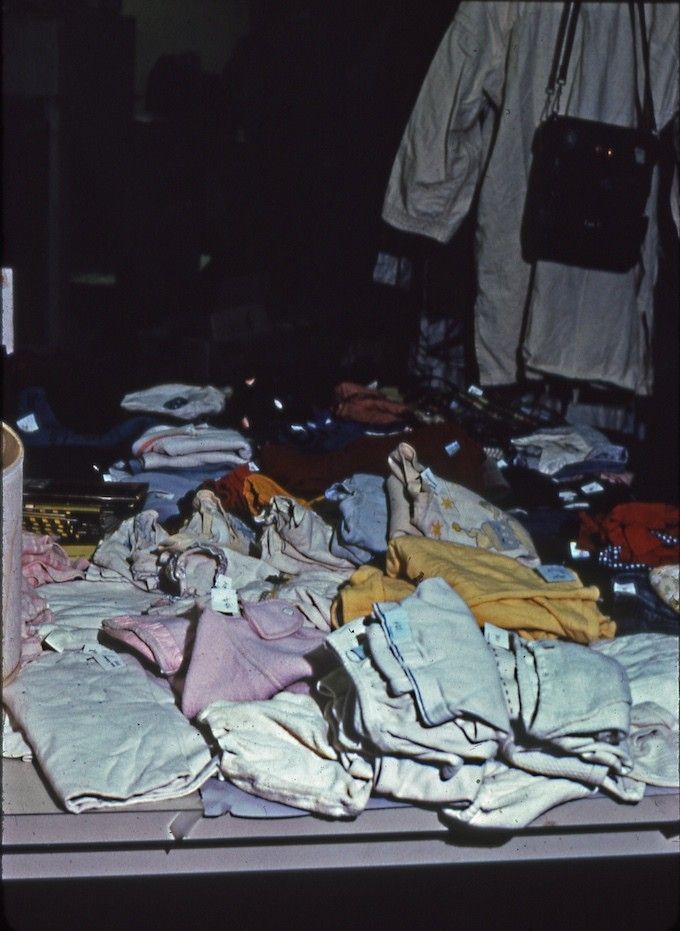

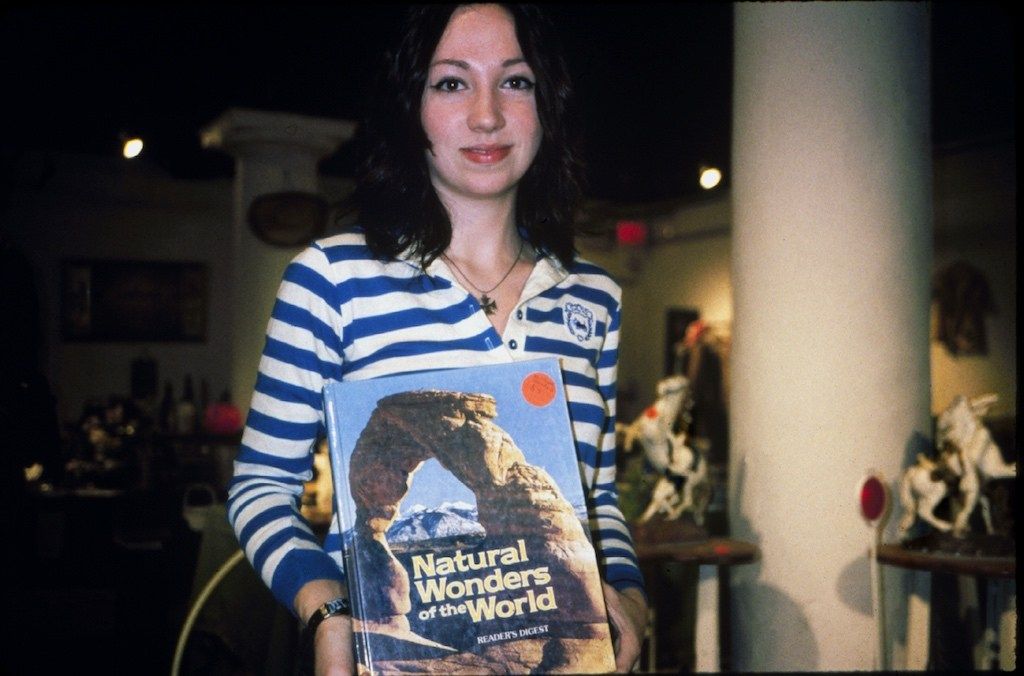

Over years of such mornings, my mother developed an analytical method for determining which neighborhoods had the best sales, those with good books, thick cotton dress shirts, and bizarre knickknacks. The Finds were often not in the richest neighborhoods, but in the aspirational middle class ones, places where a more affluent generation was tasked with sorting through their parents’ belongings after a death or a move into a retirement home. Neighborhoods where people had lived when they were young and newly married, where they bought property after they joined the law firm but before they made partner, neighborhoods that were respectable but modest.

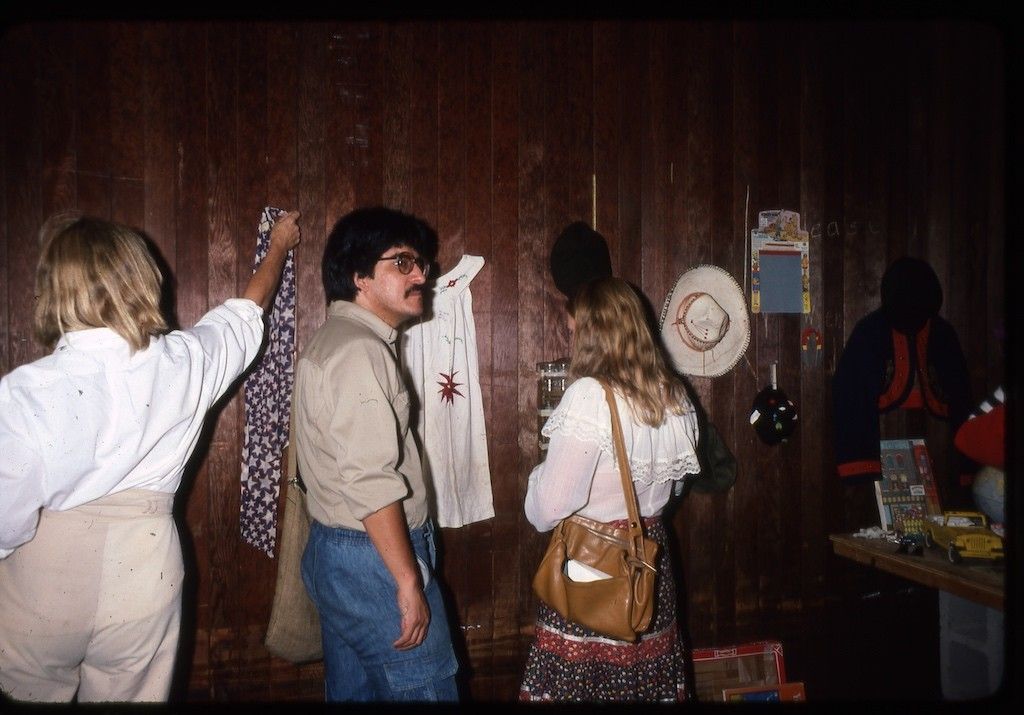

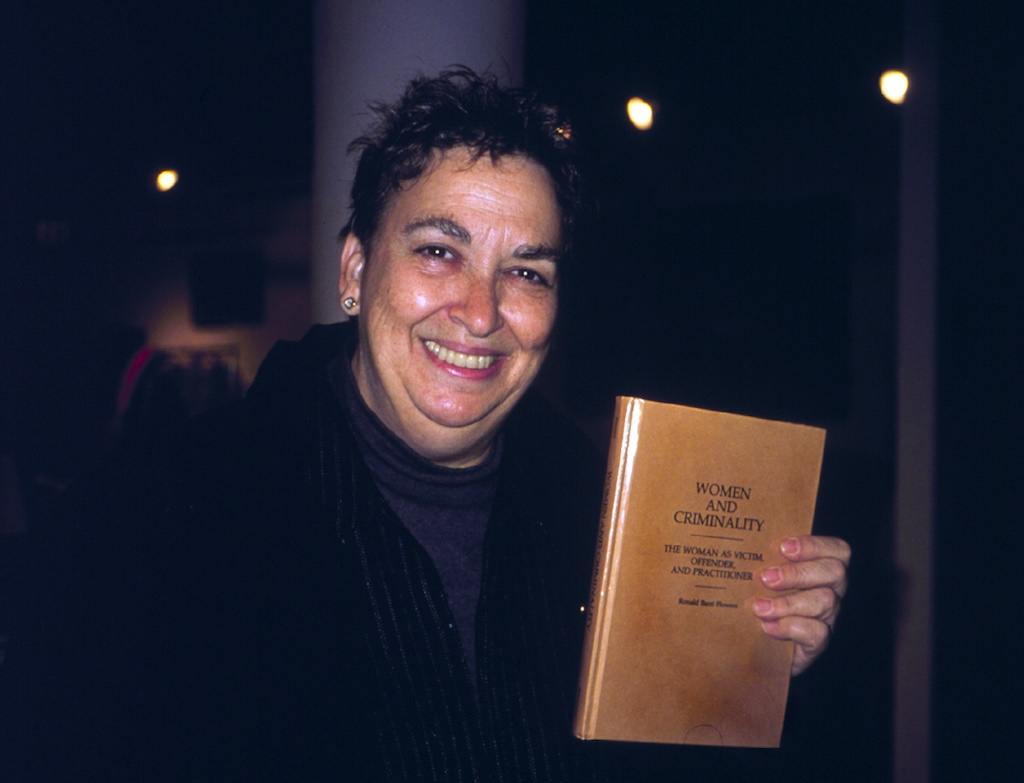

If we showed up early, people still believed in the value of their stuff. Especially at the sales of those less used to any challenge to their ideation of value, hosts were insulted by my mother’s laconic explanation that DVDs just aren’t worth more than $1 at a garage sale. If we got to a sale late in the morning, even the most self-assured banker-by-day had been deflated by hours of people scoffing at his suggestion that a vacuum used only twice was still almost as valuable as it had been the store. Time eroded confidence, but so did repeated confrontation with whoever had read the block-printed announcement in the newspaper and showed up to argue with them about the value of their possessions.

Beyond the aesthetic chaos produced in the house we lived in, the ritual also instilled in me a deep appreciation for the psychological construction of value. I absorbed my father’s quiet Mediterranean skepticism in the face of blustering North Carolina Republican assurance that this lawn-mower or that radio was top-of-line, no-question, worth-every-penny. I listened to my mother’s Southern accent thicken with an older woman selling handmade lace and then vanish when trying to buy a box set of Kierkegaard’s complete works. Each sale required a lightning-fast strategic assessment of class, of a seller’s generation, and of their prejudices. The garage sale, I learned early, is regulated by conflict between complex and highly contextual fantasies of value that are also deeply subjective.