On the evening of July 1, Kunsthall Stavanger opened its doors to Swiss artist Nicolas Party’s exhibition Landscape. The kunsthall was decorated with Party’s well-known stones, painted to resemble fruits. The visitors dined on food presented on Party’s specially designed tableware, placed on rectangular tables, while the summer light shone in on walls painted with roundly shaped trees, leaves and landscapes. It wasn’t until you were sufficiently pleased with the intake of chorizo, beats, carrots and cheese that you would venture into the adjoining rooms and meet the familiar motives adorning the walls.

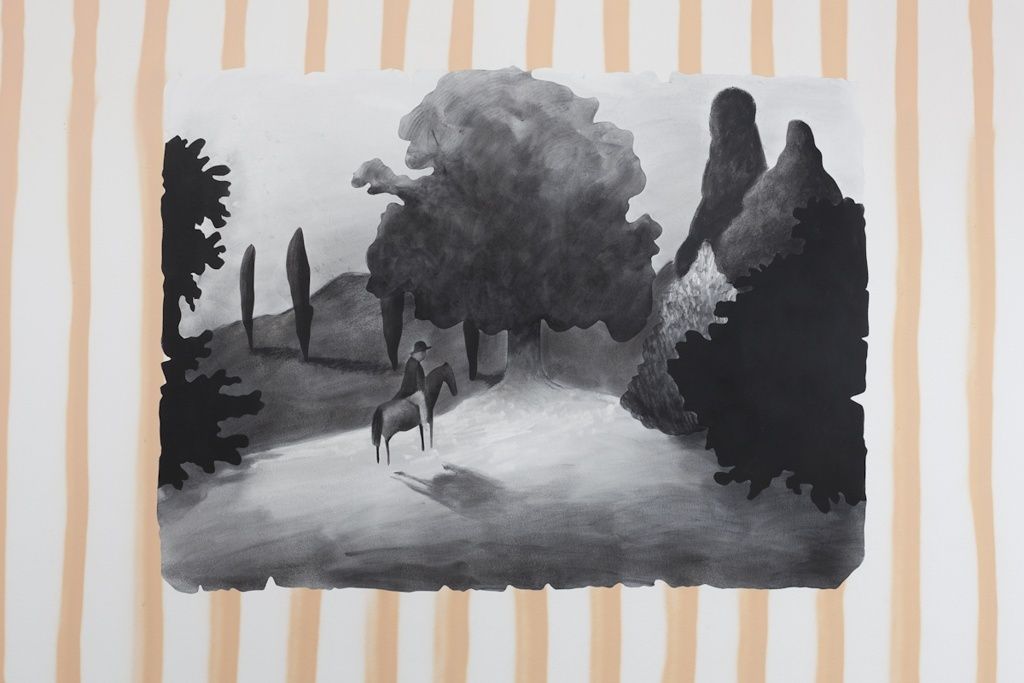

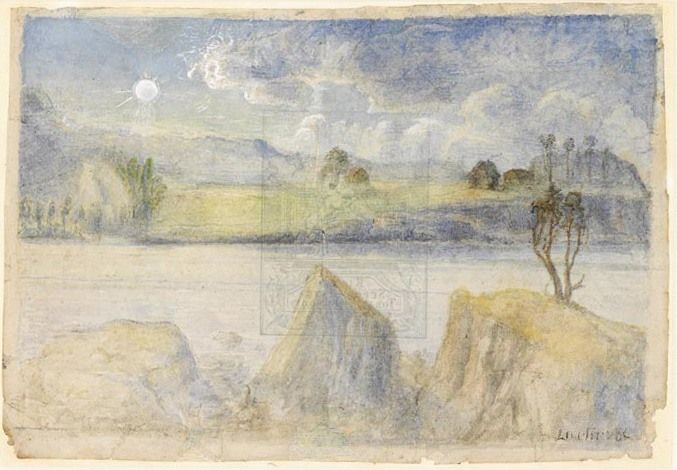

Enclosed by vertical stripes in a 1920’s colour pallet (the same decade the kunsthall’s building was completed) were the motifs of Lars Hertervig – a Norwegian painter from the 19th century. Known for his haunting landscapes, his dying trees, and his strangely curled plants, it is easy to see how Party – who often paints shapes resembling trees and morphed growths – would be drawn to Hertervig’s studies of nature, and as a consequence mimic them in this exhibition. Party first came in contact with Hertervig’s work when he visited Stavanger earlier this year to create his exhibition at Kunsthall Stavanger. Before Party was given a tour of Hertervig’s paintings at the local art museum, he had no previous knowledge or relationship to the paintings and works of the artist. We can therefor see him responding mainly to the material itself, namely Hertervig’s paintings.

The importance of physical materiality is once again rising to prominence in the world of art. As a consequence I will use this essay to ask if the ontology of new materialism can be used to understand art. New materialism is a recent development within the humanities and social sciences, but has to my knowledge not yet been applied to the fine arts. To pose my questions, I will use Party’s work at Kunsthall Stavanger.

The meeting between the work of Hertervig and the production of artworks Party made is in some ways reactionary. It carries with it questions of how an artist reads material and uses it towards the creation of something new. How, instead of engaging with the preconceived knowledge of why Hertervig painted, Party went into a dialogue with the work itself and the material the work comprises.

Diana Coole and Samantha Frost write in the foreword to their book New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency and Politics (2010, Duke University Press), that we need to return to fundamental questions about “the nature of matter and the place of embodied humans within a material world”. The reasoning behind the need for a new ontology to understand our material world is, according to the authors, the advancements in natural sciences and technologies, biotechnological engineering, and digital and virtual technologies. These developments bring with them new ethical and political concerns, leading to a need to reorient our selves in what they conceive to be a new material world. How can objects or matter help us with this? And can new materialism be used as a tool for orientation in the art world?

Coole and Frost see new materialism as a range of ontologies that can be used to deal with issues concerning mainly bio-genealogy, politics, economies and the overarching themes of the social sciences. Related to phenomenology, habitus, Marxism and materialism – concepts which has often been deployed in art – new materialism stands as a conjunction of these theories, borrowing the best, as it were, from all worlds in order to construct a new way of understanding materials and man; seeing materials as a flexible and moving substance. New materialism brings with it the idea of inter-subjective experiences of objects, meaning also that objects have pluralistic properties. To simplify and be at risk of oversimplifying, you could claim that new materialism is about seeing the world through the lens of the material, but also acknowledging how extremely intricate these readings can be given the plural understandings they evoke. Meaning that it is not so much about the material as a constant, but rather the material’s extension outside of itself.

It is important to stress that the new materialists are not concerned with matter as defined by a linear logic of cause and effect. New materialism can be understood not as not relating to inactive matter, but rather seeking out lively material, or as Coole and Frost write, “the active process of materialization which embodied humans are an integral part, rather than the monotonous repetitions of dead matter from which humans subjects are apart.” They continue by stating, “In sum, new materialists are rediscovering a materiality that materializes”. In this way we can see new materialism as also being used to understand created active matter, such as artistic creations.

At the Stavanger Art Museum, Nicolas Party was given a comprehensive tour of Hertervig’s paintings and also engaged with his biography. According to Party himself, he was intrigued by Hertervig’s representation of nature and fascinated by the way each element in his paintings plays a specific character in what Party calls “a strange post-apocalyptic story.” We see Party using the objects and his material understanding of Hertervig’s paintings in an active manner, both in the way he reads them, but also in his reaction to them – by creating something new.

If we set this in relation to post-structuralist ideas around the author-reader relationship, it is here not the single element of an author or a viewer who becomes important, but the correlating relationship (while the pluralistic reading remains important, as in new materialism). However, in the case of Hertervig-Party, Hertervig’s paintings inform the viewer, namely Party – but Party also gives new substance to the author. Party’s reinterpretation brings something new to the already completed work of Hertervig and makes us see his motifs in the setting of contemporary practice and society. As such, the paintings or materials created in the mid 1800’s are, through materials created today, telling us something about ourselves and the way that we understand the original works.

A question that arises from Party’s exhibition and similar reinterpretations of artworks is whether we can say that the value and intention of a work is constant. Or is it indeed dependent on the time and setting in which it is read? The New Materialists see matter as in constant flux; take as an example the exploding and flexible nature of atoms - the starting point of all materials. Its destabilisation can be compared to the value of a work of art. Its constant is in its materials, but because it exists in the world to be seen, the materials and their readings become destabilised, like the atoms of which it consists. In this way, the material of art can indeed offer new readings and analysis of both society and artists’ authorship. The matter is presented to us; Party sees Hertervig’s material through his own eyes, where it becomes a post-apocalyptic universe, while others perhaps would see the changing of seasons or a landscape they know from childhood. It seems that the material of art is a mirror in which we are staring at our time and at ourselves.

We identify art as a constant but flexible agent, in other words as an active material. We can include it as something that can be read through the deployment of new materialism. Coole and Frost insist that because we ourselves are made from matter, we must be materialists in order to understand the world we are part of, precisely because it is made up of matter. If we want to use new materialism to analyse art, perhaps the pertinent question we need to ask is “does it materialise?” And in the case of Hertervig and Party, the materialisation can be seen on the walls of Kunsthall Stavanger.