This approach recognizes that cities themselves are part of complex socio-ecological systems, and that bringing nature closer through the creation of urban wetlands and forests, and green roofs can provide cooling, animal habitat, and protection from erosion and flooding. Creating green infrastructure is often spoken of in tandem with the provision of ecosystem services, a kind of self-replenishing green assets that help to sustain flora and fauna (humans included). Environmental features become green infrastructure when they are strategically integrated into the built environment. Dark corridors that act as pathways for bats and other light-sensitive creatures strategically placed to connect. When random dark parks are scattered throughout a brightly lit environment, they fall short, as far as the bats are concerned, and are not infrastructural.

Infrastructure that is green, and, often, blue (water-based), pushes back against ideas of human exceptionalism by situating our species within a broader continuum of life.

Infrastructure that is green, and, often, blue (water-based), pushes back against ideas of human exceptionalism by situating our species within a broader continuum of life. Green infrastructure helps to connect people living in the heavily managed built environment with the wider world of plants, and it provides opportunities to commune with other species; mitigating some of the downsides of density, the psychological stress of crowding, and the anomie of modern societies.

Green infrastructure is also deeply pragmatic, corridors and habitats within cities for plants, animals, and insects helps to maintain biodiversity and well-placed community gardens, urban forests, and wetlands can help offset the ‘heat island effect’, sponge up water from the severe storms (that have already started occurring more frequently as a result of climate change), and provide probiotic exposure to bacteria that can help prevent infections and allergies. Green spaces in the city also provide opportunities for ‘low carbon leisure’, gratifying activities outside of consumption. When done well, spaces of urbanised nature provide recreational, as well as spiritual, benefits.

Parks for the People: Green Space and Urban Cultures

If you are reading this and thinking, “green infrastructure, that sounds like parks.” You wouldn’t be wrong, but parks come in many stripes. Many of the well-manicured leisure spaces that are passed off as parklands are optically green but lacking in biodiversity. Their lawns are subject to frequent mowing, their shrubbery is ornamental, and their trees are severely trimmed back . Parks are, traditionally, places for people, whose leisure and comfort are paramount, and parks’ role in local ecosystems is secondary. Today, we see an expanding notion of what parks can, and should, do for the societies who build and maintain them, and for animal and plant habitat.

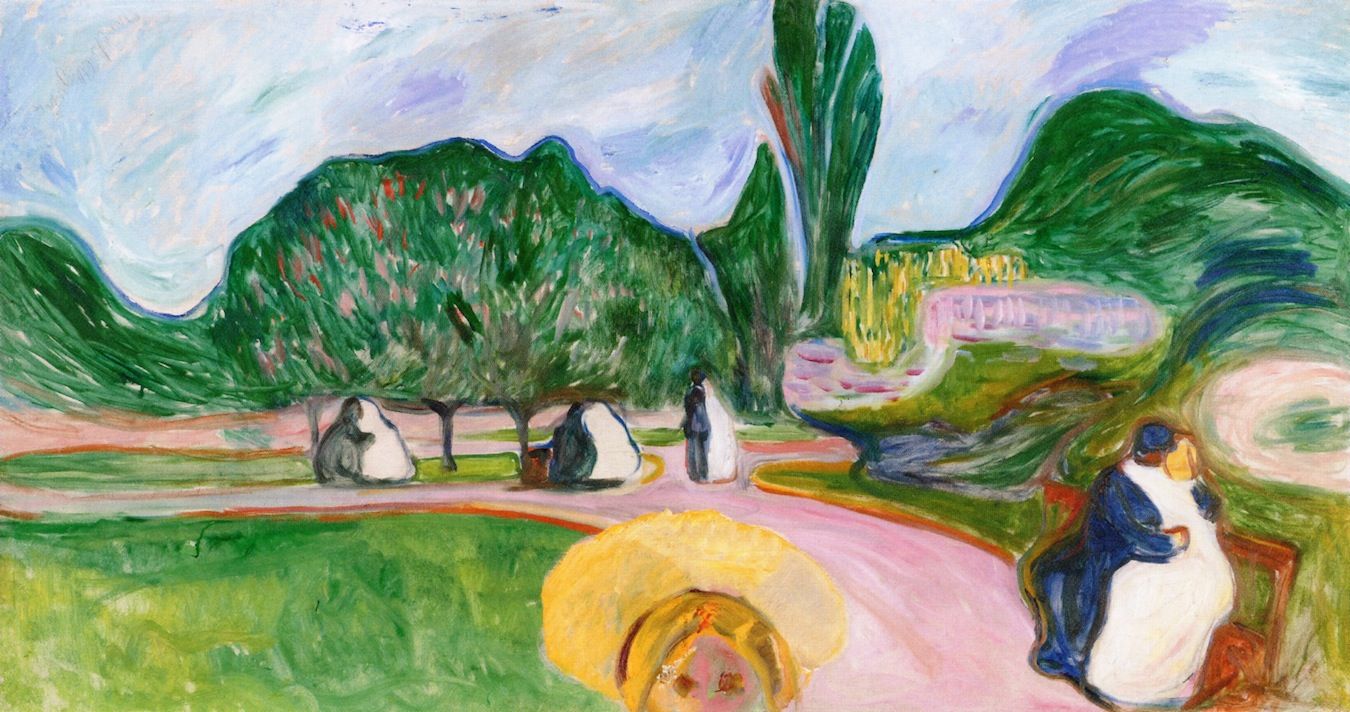

Parks provide recreational space, such as playing fields, but they also evoke pastoral visions of the countryside by incorporating winding paths and ‘naturalistic’ arrangements of trees and shrubbery. They bring bucolic landscapes close to city dwellers. Bucolic comes from the word shepherd, and one only needs to think of the idealised paintings of the early 19th century to see why this vision of the countryside was so appealing: strapping rosy-cheeked youth supervising grazing sheep presented a healthful alternative to the anaemic city kids of the era. In city parks, it was thought, children could grow strong like their country cousins.

For adults, parks presented the possibility of release from the overstimulation of city life Twisty pathways and ornamental lakes produced a a miniaturised version of healthy (and far larger) ecosystems from far outside the city limits. If the city was epitomised by crowds, hard edges , and the monotony of repeated forms, parks allowed those with leisure time to wander, think, and find themselves.

While parks were often celebrated as proof of civic leaders’ largess, with statuary around their perimeter and city crests moulded on their wrought iron gates, they were just as much the product of fear.

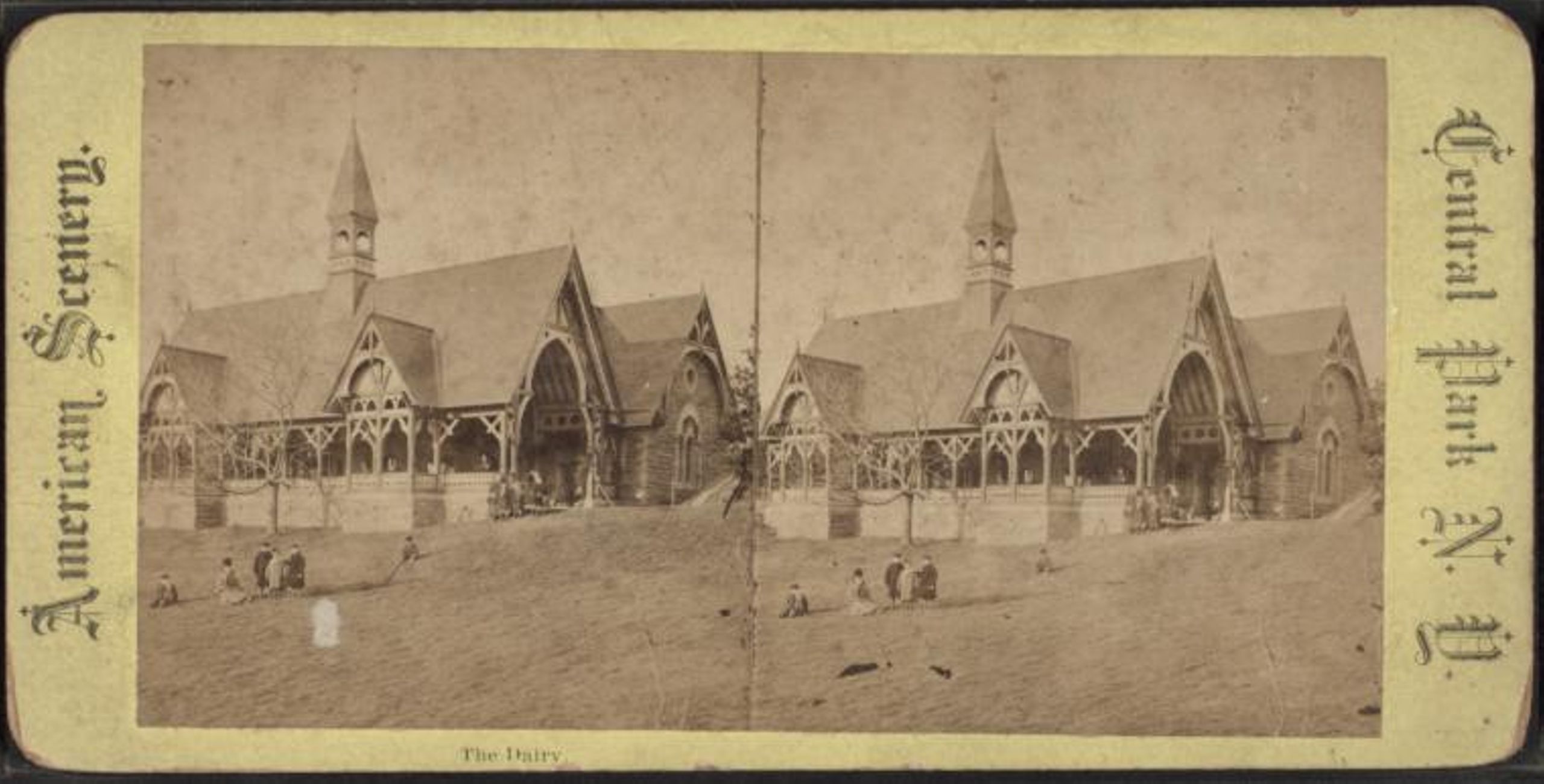

The growth of cities during the Industrial Revolution made old growth forest and swimable bodies of water inaccessible to city dwellers. In recompense for those lost acres of green, municipalities created close replicas: parks. These were often the leftovers of royal hunting estates or, in some cases, noxious land uses that had been pushed further out of the city by the growth of railroads and the advent of more streamlined production processes. Amsterdam’s Vondelpark (inaugurated in 1865), Paris’s Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park (both started in 1867) were all former quarries and brick-making yards. Their creation, in the mid-19th century, went hand-in-hand with the growth of municipal governments and the increased provision of services for citizens. While parks were often celebrated as proof of civic leaders’ largess, with statuary around their perimeter and city crests moulded on their wrought iron gates, they were just as much the product of fear. Especially in Continental Europe, where wealthy burghers had witnessed the French Revolution followed by the revolutions of 1848, there was a strong desire to improve the conditions of the working classes and thus keep uprisings at bay. Parks, with their winding paths and dispersed attractions, were subtly designed to undermine opportunities for mass gatherings and political rallies, but they were also created to alleviate mental and social pressures that were thought to kindle the revolutionary spirit.