I am building an archive of bread. This material takes on various forms and mediums.

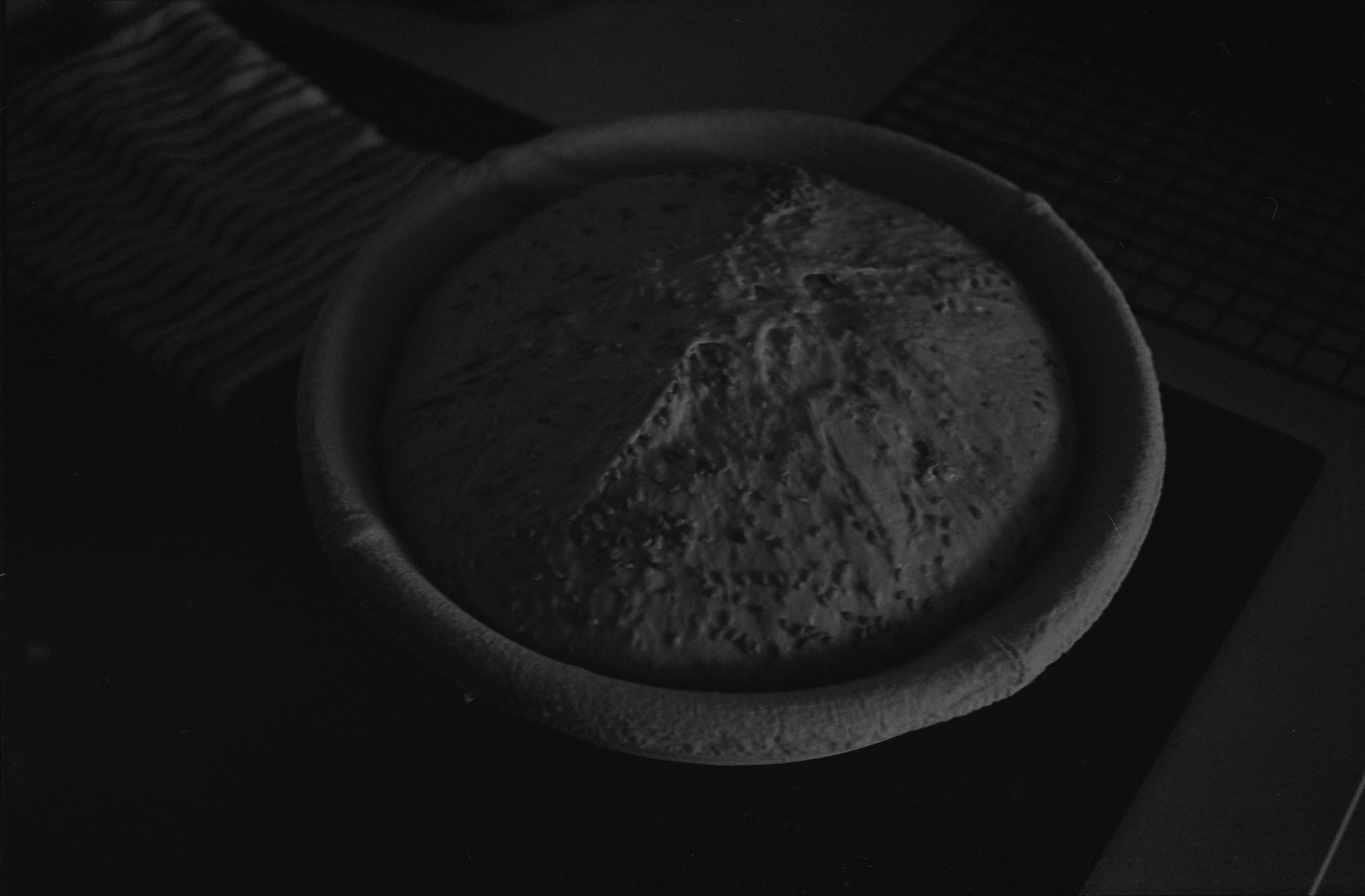

Sometimes it’s simply bread—baked, fermented, shaped by hand. This is part of my everyday practice. My hands have become part of this archive — remembering gestures, folding dough, shaping forms. This embodied knowledge is carried not only through objects but through these repetitive, daily acts. During my research on bread, I often look for old recipes, including those from my Slavic ancestors. I’m particularly interested in the historical practice of adding various ingredients to increase the bread’s volume — in times when flour was scarce, fillers like birch bark, wild plants, or potatoes were used.

Other times, bread becomes a sculptural material and baking a method of research. I am fascinated by using bread as a medium in art and as a way of expression. Often, the sculptures take on a baked, dried, almost blackened form, preserved with large amounts of salt. Other times, they remain edible objects, open to consumption.

A significant part of this archive involves reviving forgotten traditions, such as the Slavic bread figurines called Nowe latka (“New Years”), traditionally baked in some regions of Poland. These small animal-shaped breads were traditionally baked around the New Year period and held symbolic and magical meaning — they were believed to bring life, protect against misfortune, and ensure abundance. Made for each household member and animal, they were shared and eaten as part of a ritual of coexistence and care. I see them as small deities. By recreating them in exhibitions, I aim to preserve and transform their power, breathing new life into this ritual.

The archive also includes my research folders filled with archival photos, screenshots, documents, and stories and fragments of memory related to bread, grain harvesting, unusual bread forms, bread sculptures, and bacteria.

Part of the archive is photographic documentation of my process. I often use analog photography because I love its materiality. I feel it complements this subject well. These photos often hover on the edge of time — it’s sometimes hard to tell whether they were taken recently or decades ago.