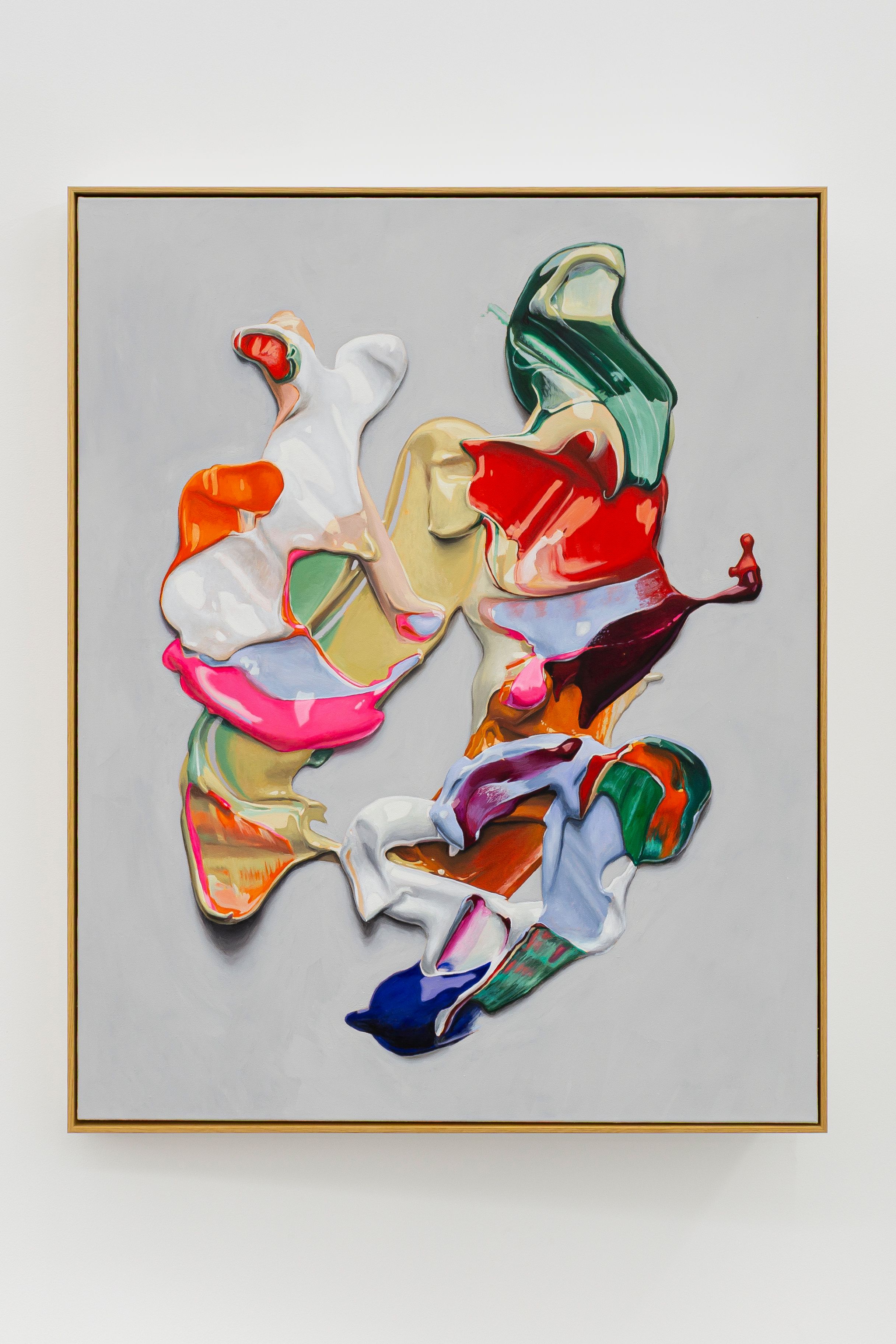

The paintings on display here are made using a method that Varpe has been fine-tuning for years, and he considers them a continuation of this much larger body of painting. It involves a swift, almost automatic laying down of blobs of mixed and unmixed paint in generous, viscous layers onto small-scale pieces of board (he refers to them as ‘the miniatures’). The immediacy of these miniature compositions is of importance to Varpe, as a kind of gearing up to what follows, which is conversely a much longer process of a slowed down, curious, and particularly attentive form of looking. He says that a miniature is produced in 10 seconds, while a month is spent on each painted ‘copy.’ Out of all the miniatures produced in one sitting, he selects a small number that he stages for photography, paying special attention to the topographies of the painted surface, which he enhances with light and shadow.

A commonality between them that is not as immediately apparent as their shared subject matter is that he lights them from above. This is a reference to classical painting tradition and museum display, where the light, as if divine, is cast upon the painted subjects and the painting itself, from above. Once the photographs have been taken, Varpe begins his search within them for qualities that motivate their meticulous reproduction on canvas. Every painting comes about in this way.

But something has changed. As with the choice of lighting, the colour palettes too have tended to be indexical, referencing painterly tropes and historical colour palettes, or even the colours of one specific painting. An example is the French impressionist Gustave Caillebotte and his 1884 painting Homme au bain / Man at his bath. Caillebotte’s depiction of a naked, bathing man challenged commonly held attitudes toward masculinity and gender at the time. Recent art historical approaches to his oeuvre speculate on his sexual orientation and whether his choices of motifs can be understood as subtly political. There has been a sense of meaning for Varpe in paying homage to artists like Caillebotte, and considering them alongside, even overlapping with, his own biography. After his mother’s passing in 2024,however, Varpe has observed that his choice of colours is shifting ever closer to home, so to speak, and further from their analytical, art historical, and conceptual basis. This is not a categorical departure, or a break, but a slow-moving, affective readjustment. If a colour can be thought of as a memory reservoir, then what it evokes is already in us.

Throughout the month of August, Varpe, fellow painter and friend Apichaya Wanthiang, and I sat down for a series of conversations, guided by our curiosity about whether a different articulation of the stakes and vulnerabilities within these works could emerge between us. We shared a sense that in the practice of looking again (and again, and again), something could be revealed to us: questions of subjectivity, memory, identity; processes of understanding, of coping, and of accepting. A practice of re-vision, a rehearsal in re-viewing, an exercise in re-seeing – of gjensynsøvelser. What follows is a recounting of some of these conversations.