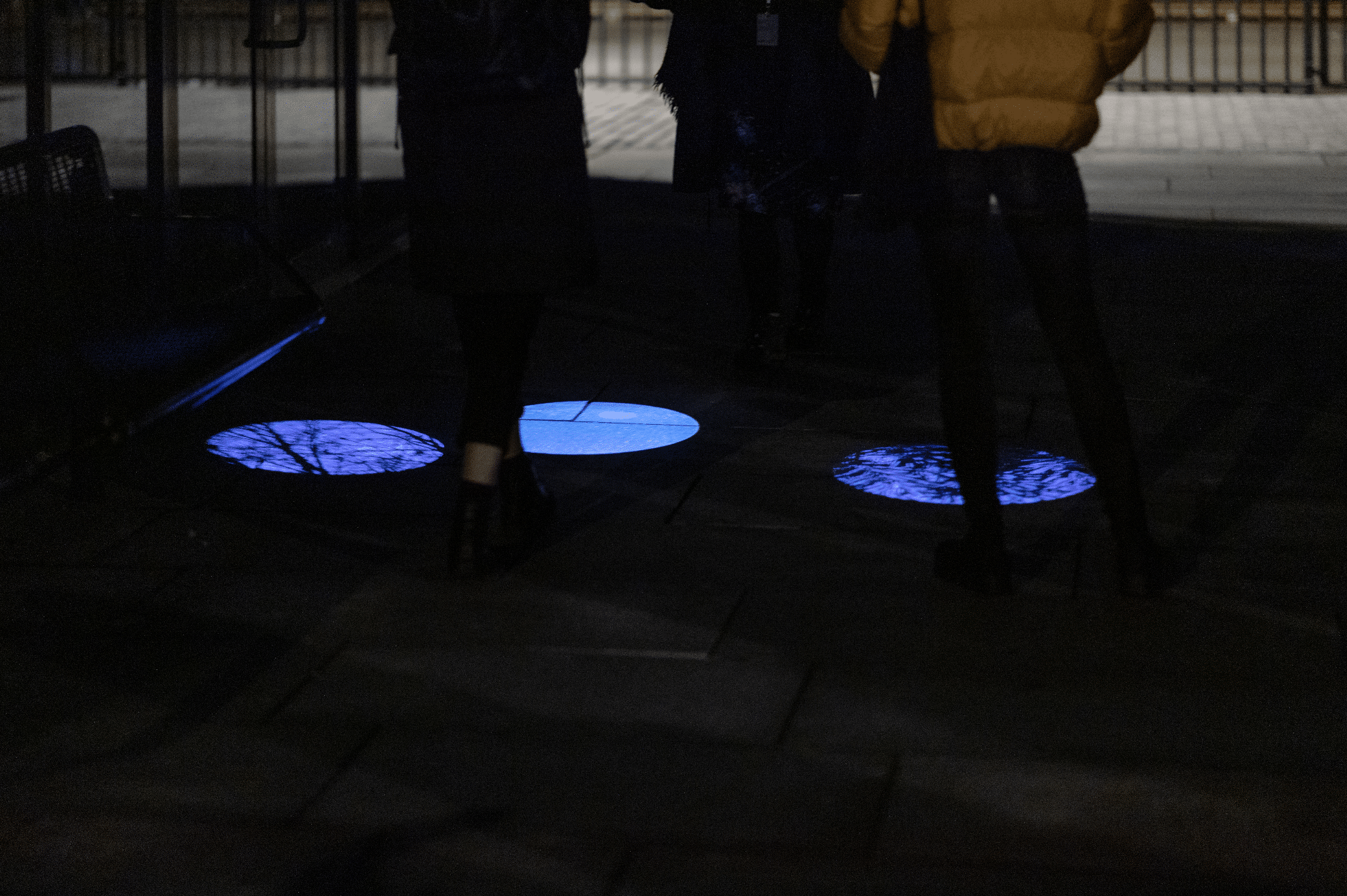

Among the newly commissioned works were Saara Ekström’s Beacon (2019), a guided walk with three handheld projectors and a soundtrack of decelerated singing of a nightingale. Coupling art, technology and public space, the piece neatly aligned with the disposition of Screen City. Filmed on 8 mm and transferred to a digital format, images of endangered wildlife captured at Finnish nature reserves were projected onto the streets and buildings of Stavanger’s harbour area as well as the participants of the walk. Following the guiding light shone by Ekström’s Beacon, biennale goers and city dwellers who accidentally came across the performance were thus granted a glimpse into idyllic scenes of nature on the brink of disappearance.

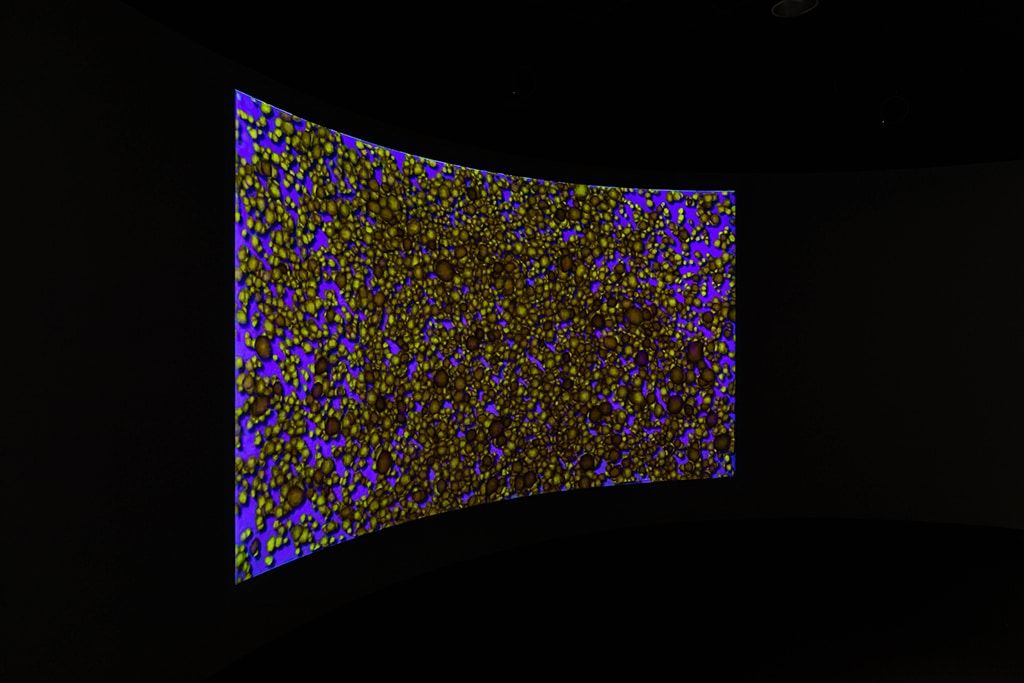

A familiar format from the previous editions of Screen City was continued through collaboration with the Organ Night (Orgel Natt) at the Stavanger Concert Hall, this time featuring Michelle-Marie Letelier’s and Kalma’s audiovisual Caliche Crystals (2019), performed in collaboration with organist Nils Henrik Asheim, and a screening of Marjolijn Dijkman and Toril Johannessen Reclaiming Vision (2018) that was adapted for the occasion to feature a live soundtrack by electronic musician Henry Vega and cellist Jan Willem Troost. Filmed with a microscope, the cinematic Reclaiming Vision played out like an action movie with nearly-transparent microorganisms as leading characters. Peering into the lifeworlds of these unlikely heroes, part cultivated in a lab and part sampled from brackish water at the mouth of the Oslo fjord, illuminated the profound extent to which aquatic environments are teeming with life and affected by human activity.

Screened at the Chapel of the Stavanger Cathedral, O Peixe (The Fish) (2016) by Jonathas De Andrade, narrated a dreamlike scenario played out in northeastern Brazil by fishermen of Piaçabuçu and Coruripe. The camera follows men that, instead of swiftly and mercifully bringing the life of their catch to an end, willfully embrace and stoke their prey as it slowly takes its last breath. Obscuring the more critical undertones of domination and exoticism inherent in the piece, the sacral setting of the presentation gave prominence to the spiritual aspect of the ritual.