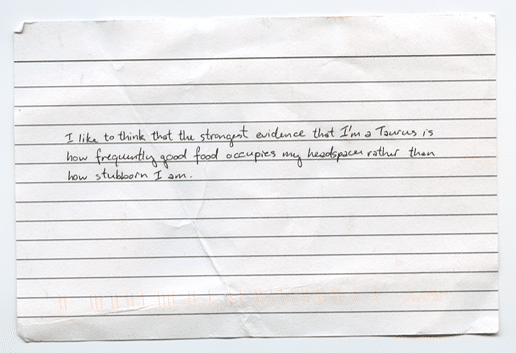

I was really fortunate that from a young age, my creativity was nurtured. That gave me a lot of freedom to explore more creative approaches not just for expressing myself, but also in how I think through the world, how I learn, and I was really fortunate to have parents and teachers who supported that. From my BA, I was mentored and encouraged by two professors in particular, Laurel Woodcock and Sandra Rechico, who really believed in me and pushed me to be involved in the local scene. As a very naïve 20 year old, I felt so capable because I had so much support behind me. The generous support from my MA professor, Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and my thesis advisor, Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir, were crucial throughout my time in Iceland. So many strong women continue to unconditionally shape and influence who I am, and I’m very mindful of that privilege. My parents have always been supportive. Neither of them are artists, but I do have artists on both sides of my family, so maybe it does run in some veins. I didn’t personally know much about the art background of my family until I was an adult, but it’s something that I very much cherish today. In terms of the concept of care in my work, that was bubbling for a while but I perhaps didn’t have the vocabulary or experience to really realize what was going on in my much earlier work. I think the work about care that I’m doing now was really spurred on while I was in Iceland. I really struggled throughout my MA. I was going through a period of grief after losing a close friend and not really understanding what was happening to me psychologically while also adjusting to living in a new country. Iceland is culturally very different from Toronto. I was trying to understand care - or the lack of care - that was happening in a different sense than I knew. These things were at the surface of my day-to-day life, and that obviously affected the work I was making. I was there as a full-time art student so that was all I was thinking about. The hospitality focus in my work came from a summer I spent working at Hospitalfield, which is an artist residency in Arbroath, Scotland. I was being hosted by the team at Hospitalfield as their summer program assistant, but was also responsible for hosting the residents coming in, and taking care of those logistics, all the while living together in one massive house. For me it was this interesting dynamic of being wedged between a host and guest all the time, and having to take on and accommodate different roles at different times. I was able to bring these thoughts into my thesis year in Iceland. I found so much theory and research that I knew would take much longer than a single thesis to unpack. This eventually led to my time as a researcher at Glasgow Women’s Library (GWL), which is where I really dug into my research on feminist hospitality in relation to radical care. I was also fortunate to work closely with Caroline Gausden, who is the Development Worker for Programming and Curating at GWL, and whose research and interests lie in similar themes. I had the time and space to let that all explode into my current practice.