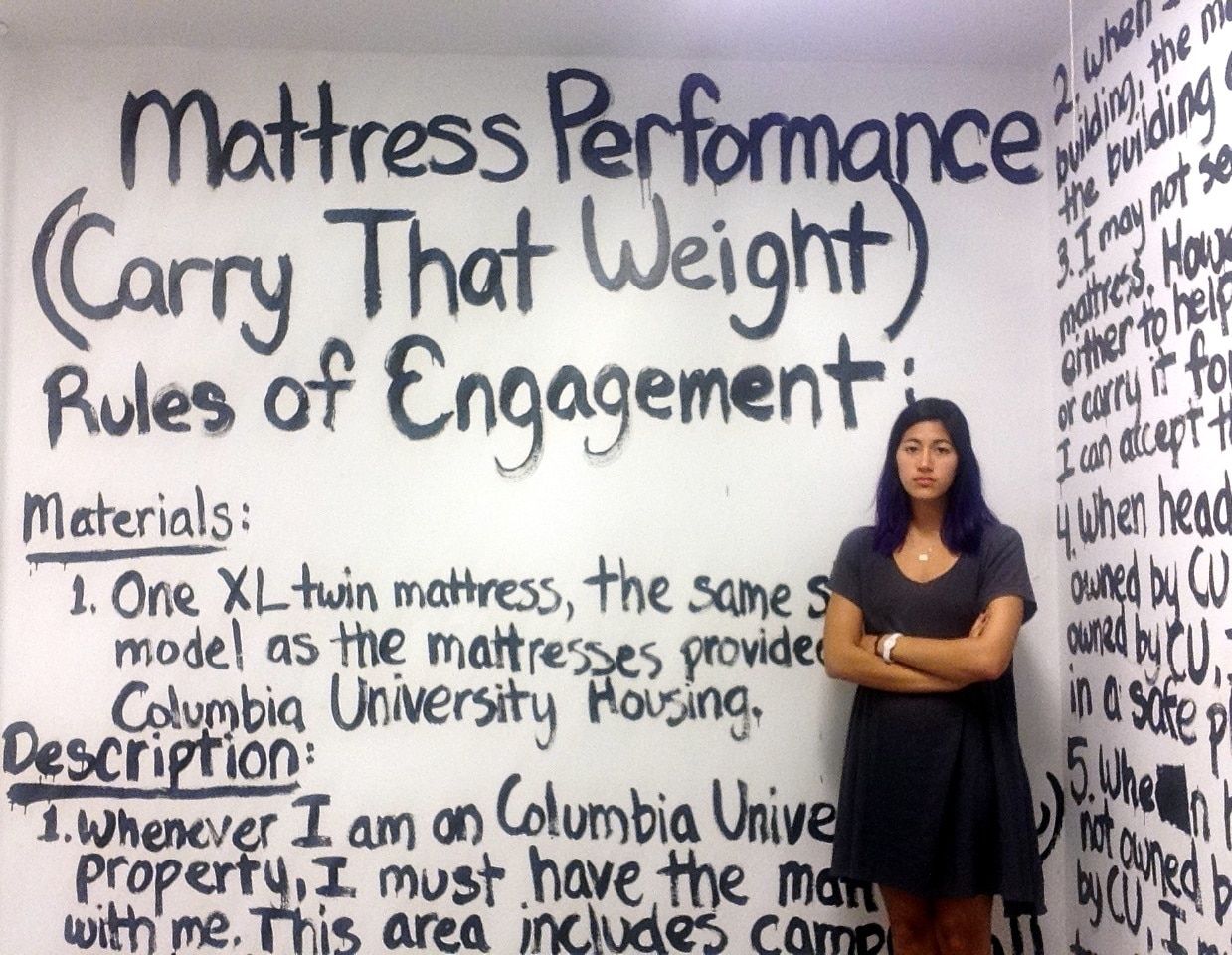

More specifically, Somatic Experiencing, commonly abbreviated SE, has become increasingly popular as a tool to move through sexual trauma, birth trauma, and abuse. I was interested in SE as a lens through which to view current body-based performance art dealing with the #metoo movement. With this understanding in mind, I hypothesized that body-based performance offers the most apt discourse on and processing of our current reality and collective trauma(s).

The skin is our largest sensory organ. There are more neurons in our gut than in our brain. Recent studies suggest that trauma (as well as pleasure) is stored not in the mind, but in the body itself, and that haptic therapies might be far more effective methods of healing than traditional talk therapy. At heart most people know this. A specific smell, sound, texture, or play of light can bring back vivid memories in more shocking detail than an image or retelling of the event, and thus can make the experience more immediately accessible.

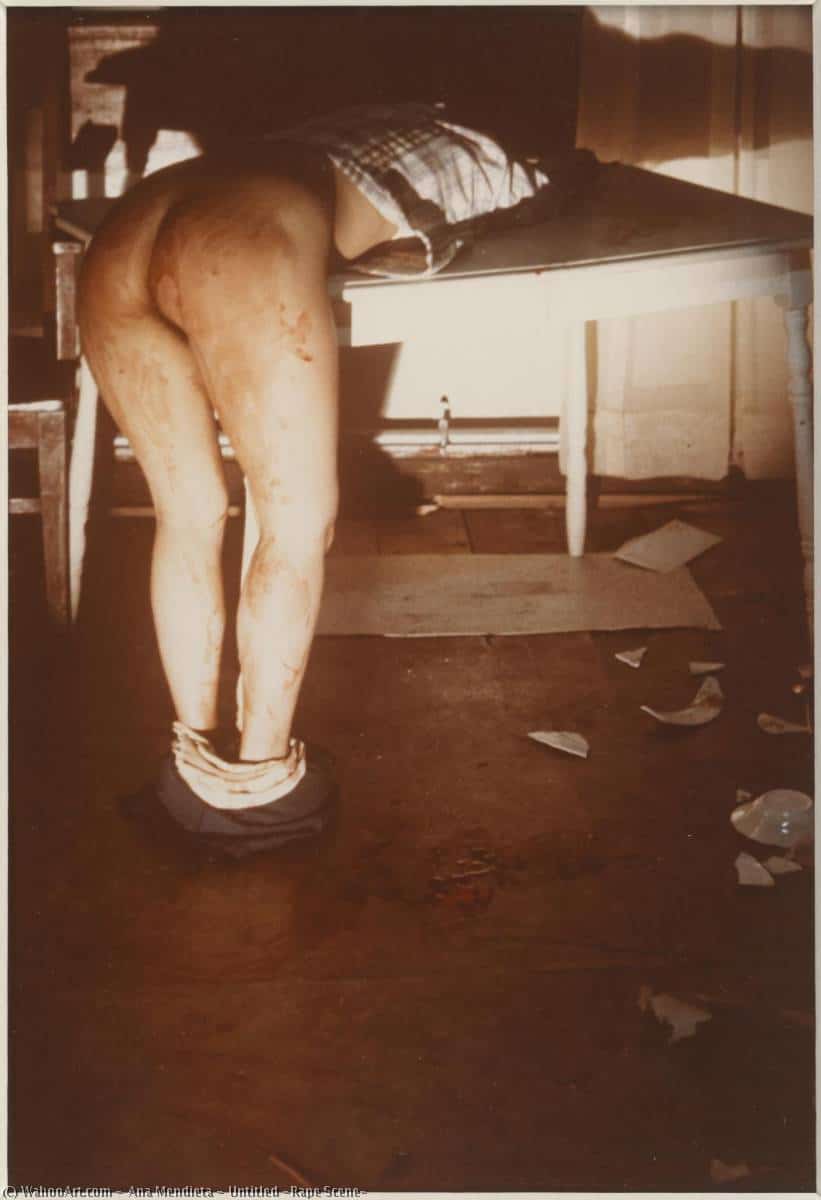

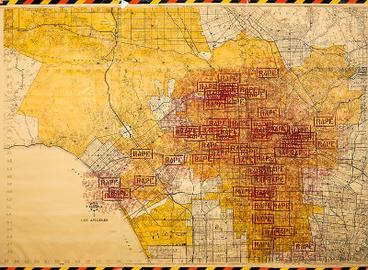

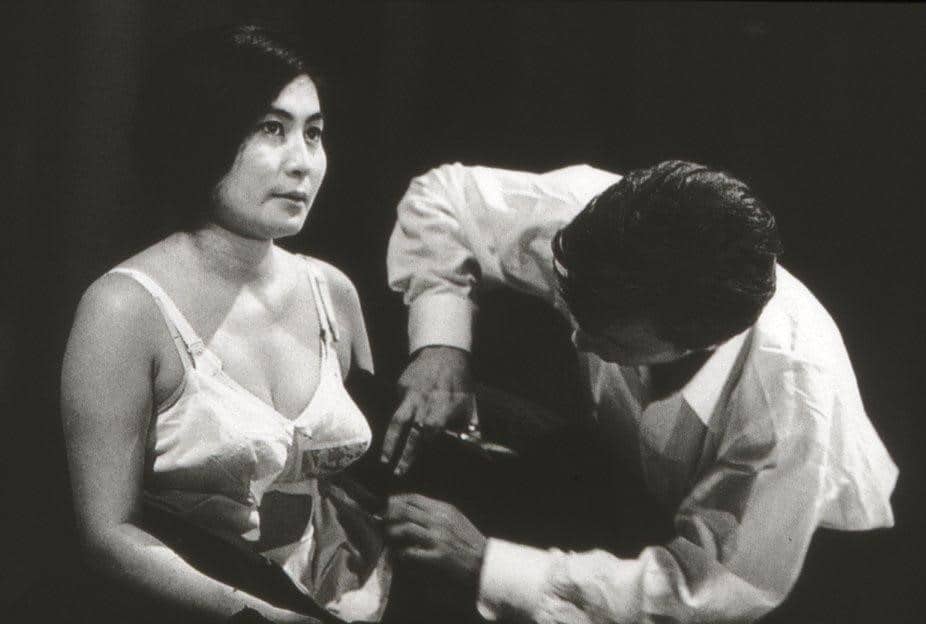

I googled, I searched, I asked friends and colleagues. I posted an open question on social media. I referenced major art magazines. I didn’t find anything. Or rather, I found a remarkable absence. Where are the body-based performance pieces addressing issues of power dynamics and sexual predation in the workplace? There were musical numbers, theater performances, street-level actions, and several strong visual art initiatives in the US, Norway, and around the world, but I found next to nothing in performance art directly addressing current issues of the female body under threat. Am I ignorant? Am I not looking in the right places? Not asking the right people? Regardless, with #metoo taking over headlines in the last several years, surely related performance art shouldn’t be a niche interest?