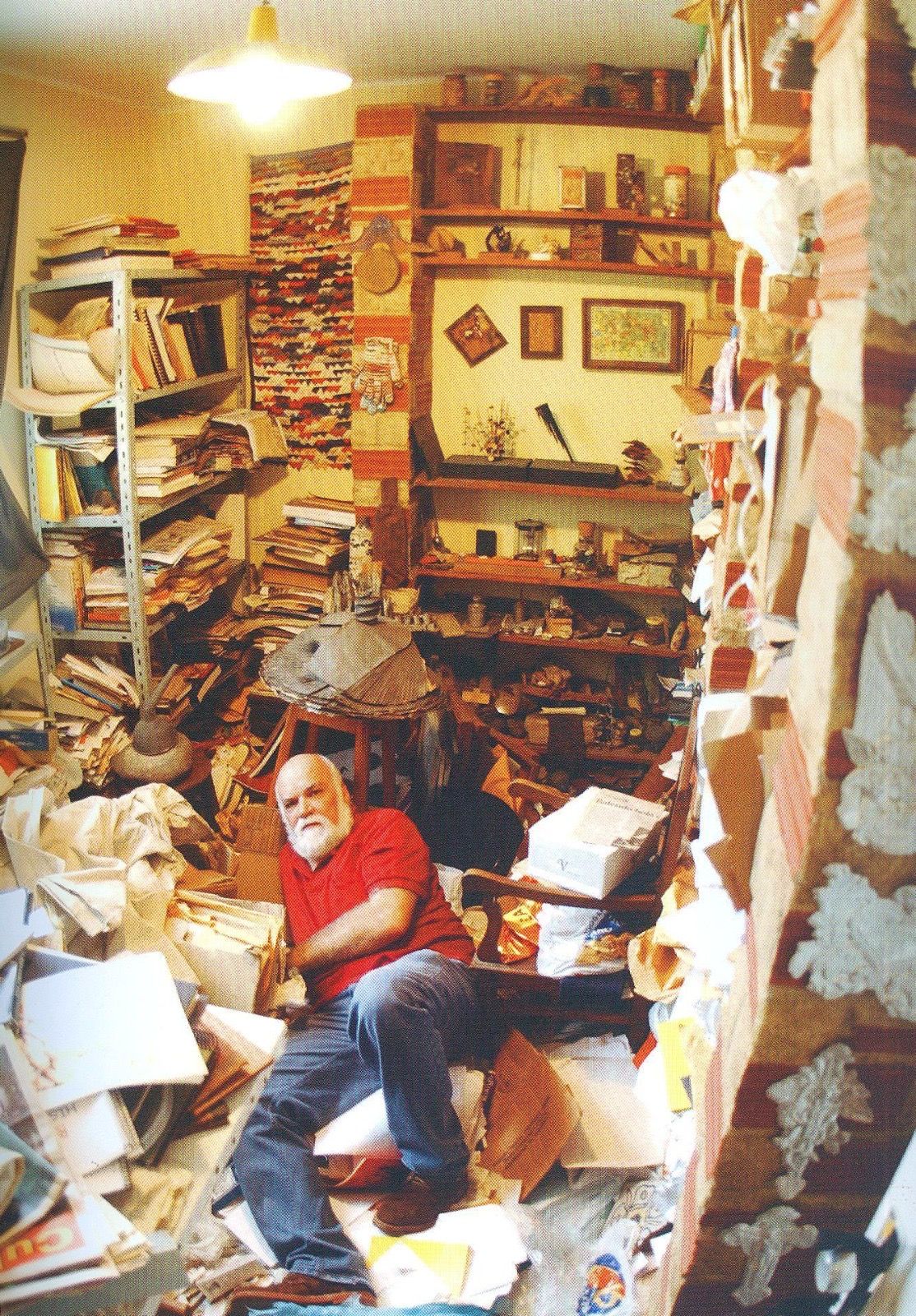

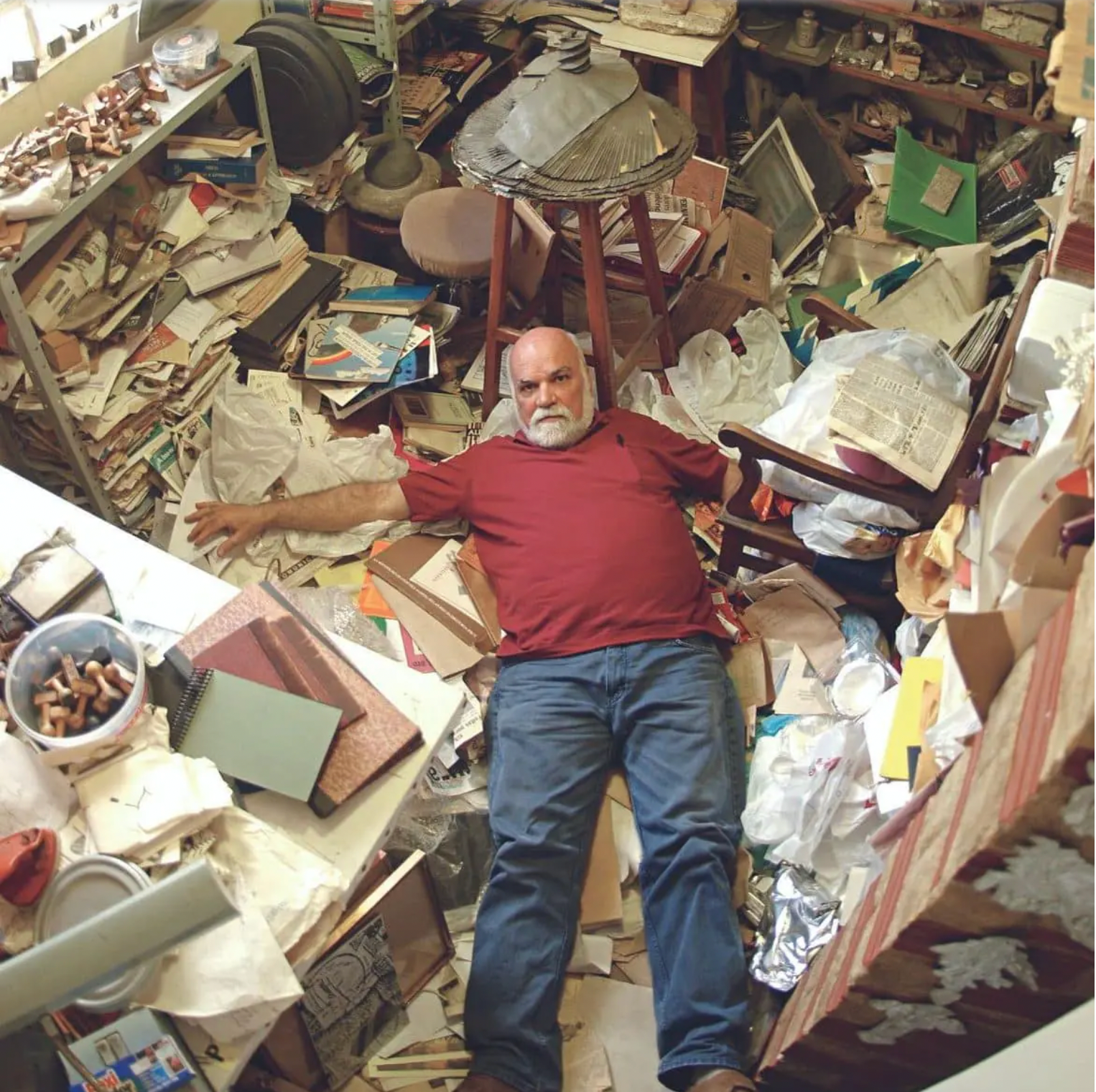

Working with Paulo Bruscky’s personal archive of artist books and engaging with the public library collection presents a fascinating encounter between two very different ecosystems of knowledge. Bruscky’s archive is highly idiosyncratic — shaped by his life, networks, and the experimental ethos of mail art and conceptual practices in Latin America. It carries the marks of a lived, embodied practice, where classification is often porous, and the story of each book is inseparable from the story of how it was made, exchanged, or acquired.

By contrast, the Sølvberget collection is embedded in a public institution, operating within cataloguing systems that prioritize accessibility, standardized metadata, and preservation protocols. While this allows for a broad, democratic reach, it also necessarily flattens certain idiosyncrasies in favor of legibility and order.

I expect the dialogue between them to generate both insights and frictions, questions about what gets preserved, how access is granted, and whose stories are made visible. It will be an opportunity to reflect on how artist books can exist simultaneously as works of art, historical documents, and living agents within different systems and how each context shapes the way we read, interpret, and value them.

In this space of encounter, friction is a fertile ground for fabulation, a place where the strict order of institutional systems and the fluid, personal logic of a living archive can rub against each other, sparking new narratives, speculative readings, and imaginative futures for what an archive of artist books might be.