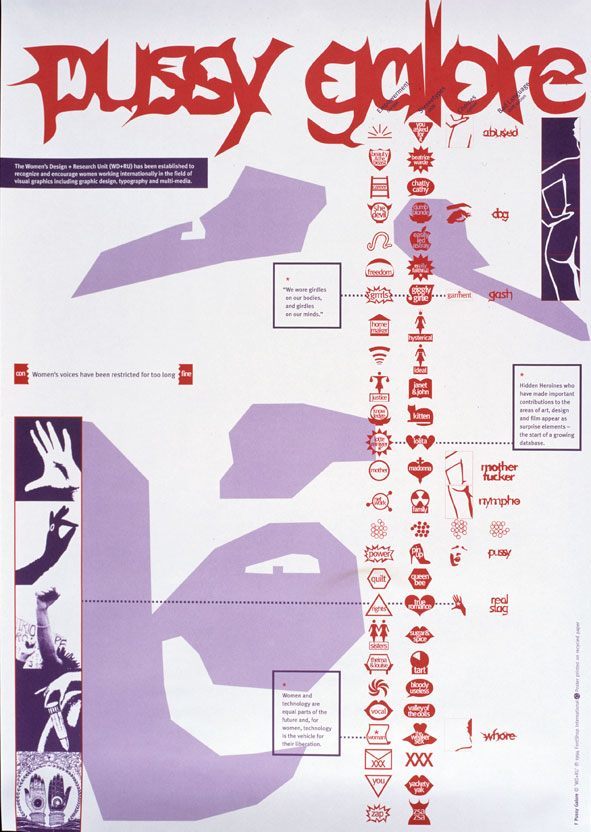

If we declare that it is the form that is to be followed, that also seems to be the demise of the strategy. But if we say that the form should be a gesture, as Falagara describes it, it is a matter of assuming the role of an enabler, as a co-creator of meaning, where the designer works in a performative dimension.

Even though designers who work with a critical approach have abandoned the notion of an objective form, they have nonetheless retained the idea of social responsibility and the desire to take such responsibility, at the same time as they reenergize the content of the message being conveyed. In that manner, the designer also has a subjectively intrinsic value invested in the form, one that is not autonomous but is a partner to feminism’s messages.

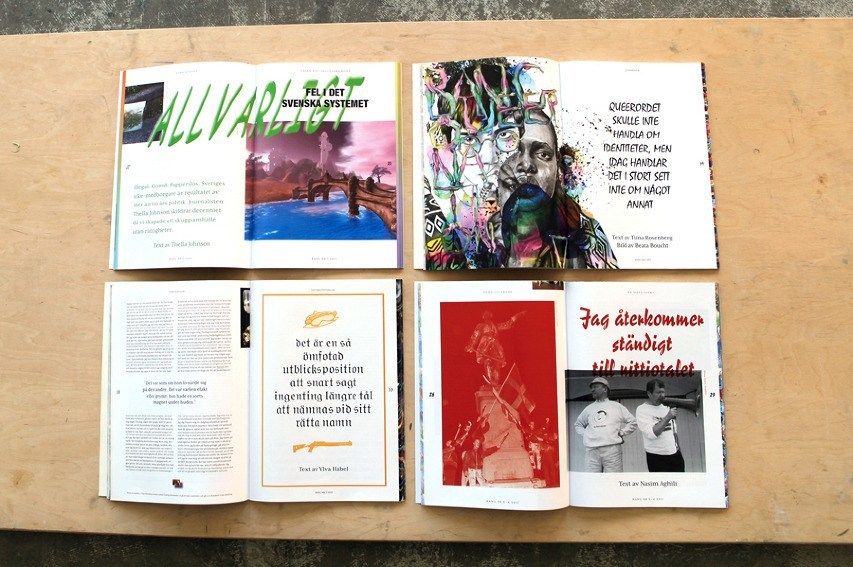

In other words, the new feminist struggle is a matter of presenting its ideas not only through the message but also through the form.

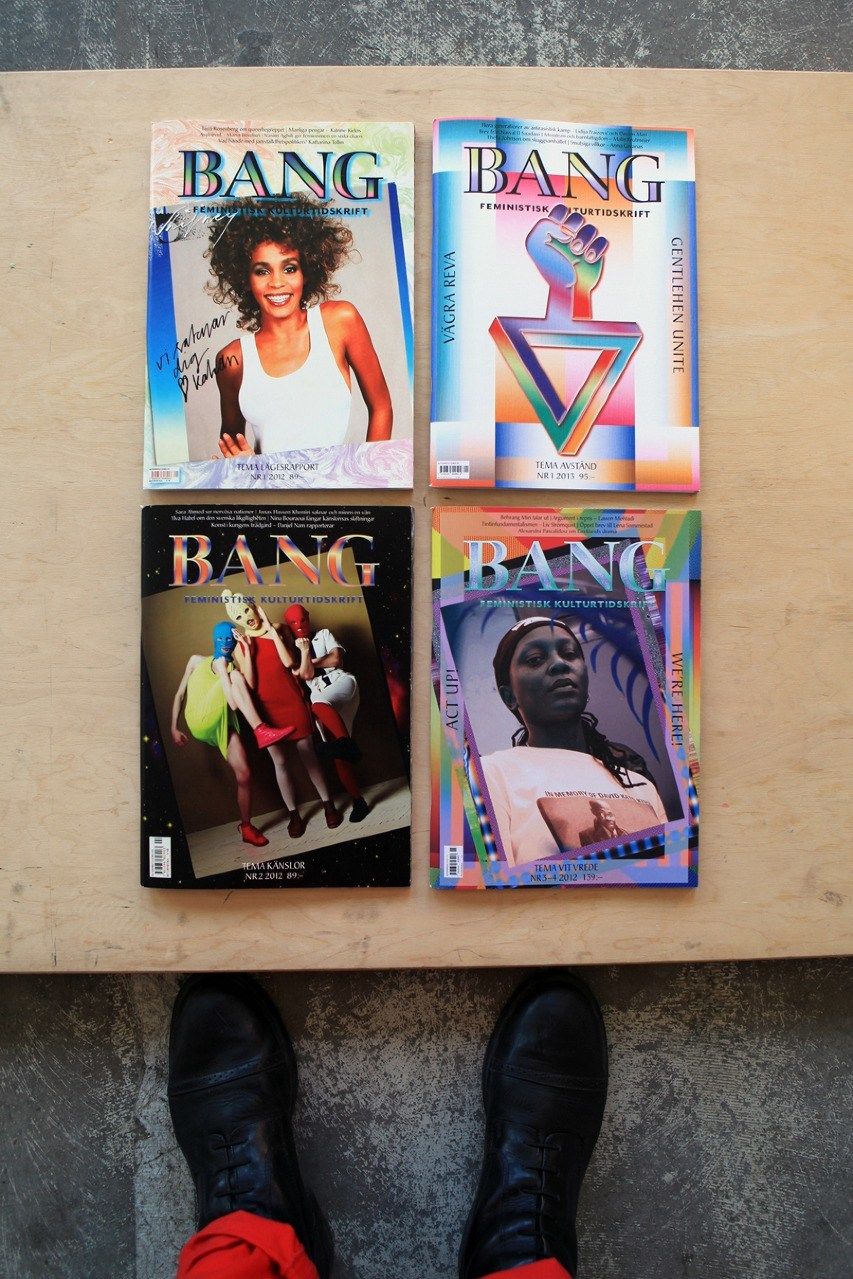

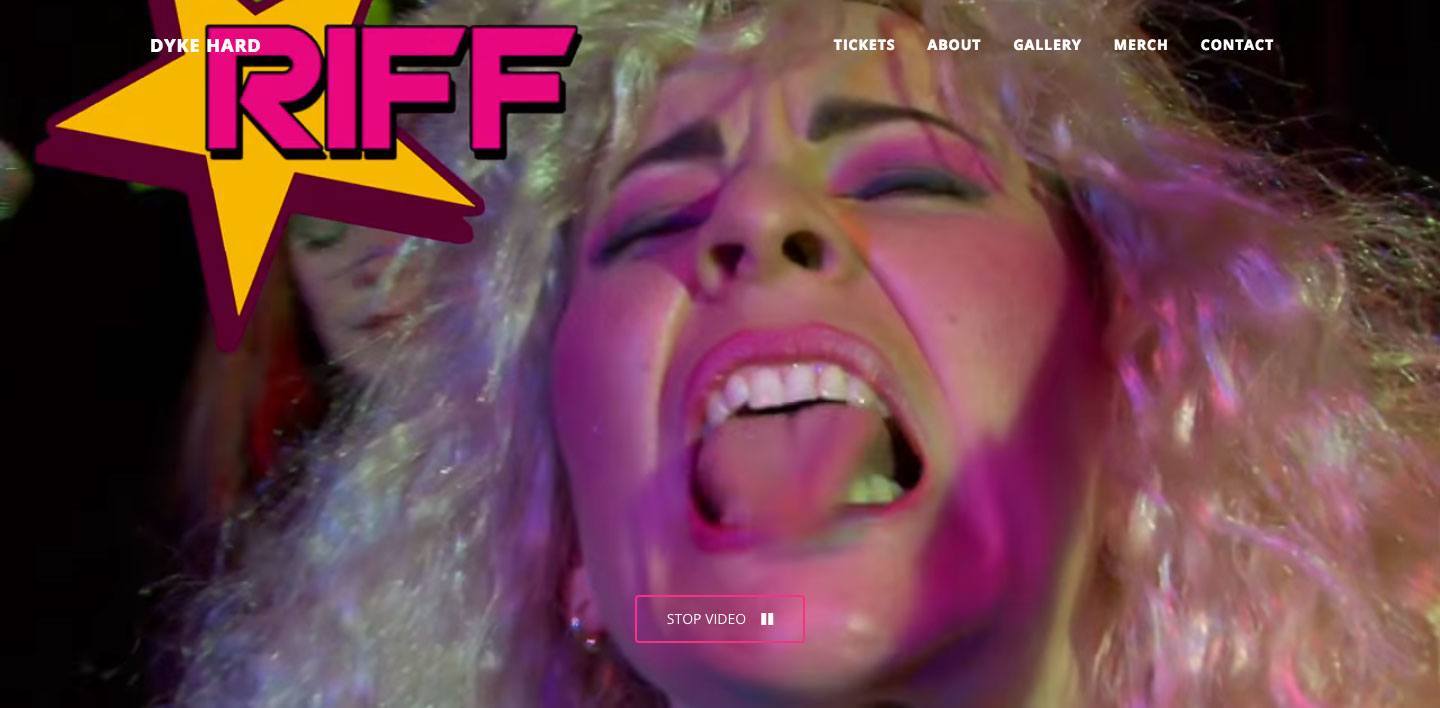

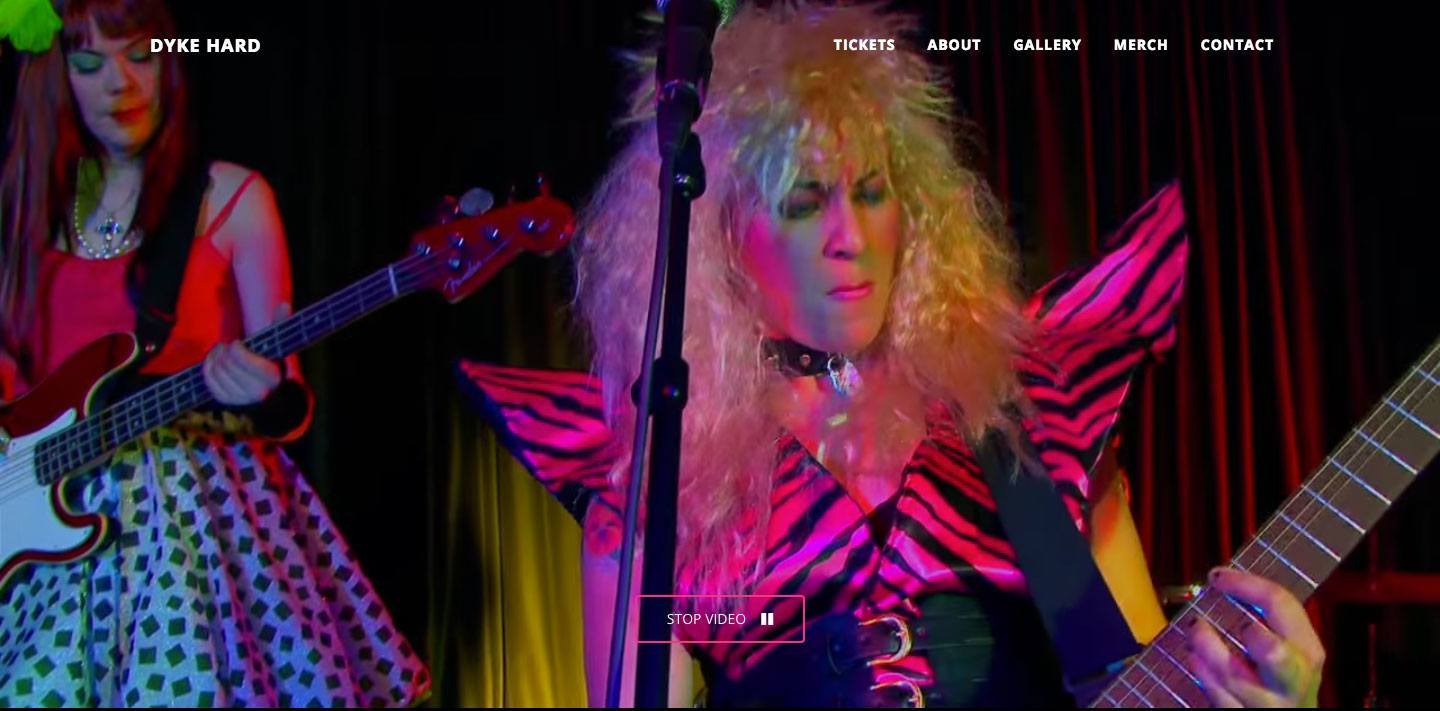

Dyke Hard

Let us return to the world of movies. Konstfack in Sweden is currently in its third year of organizing a master’s degree program that focuses on norm criticism, as led by Johanna Lewengaard and Joanna Rubin Dranger. The same program was previously known as “Storytelling” and was already at the time underpinned by some of the same ideas concerning challenging normative and discriminatory hierarchies.

One of the results of the Storytelling program was the film Dyke Hard (2014), a celebration of the norm-critical discourse in the style of John Waters. The airplanes have been replaced by motorbikes, the women are no longer only white and dressed in tight-fitting clothes—and they don’t take orders from a white, middle-aged man, as in Goldfinger. “Just get on the bike, dyke!” one of the characters yells to another from the back of a motorbike.

The message here is steeped with feminist ideas, from action and plot to portrayal. It includes the designer’s role as communicator, author, and enabler alike. And it demolishes the heteronormative not only with content but with form.