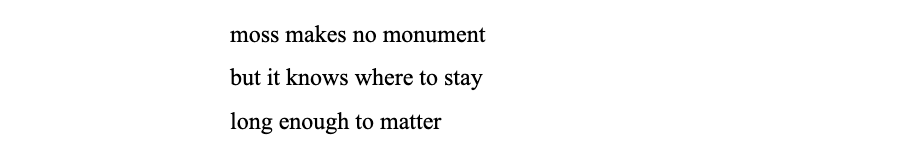

I have gotten into the habit of saying hello to plants. Not every plant. Plants that I might not have seen in a while – the first snowdrop as winter accommodates. Or, perhaps, a plant I was not expecting to see.

Hello oak, I said. Not aloud but under my breath – a gentle, quiet gesture. I find trees so affecting. Their stature, presence. Their embrace.

Oak moves me. Moves me to stop and say ‘hello’. To pause and observe for a moment. To dwell under their canopy.

I stopped to catch my breath and thought what’s in a name?

I think of British nature writer Richard Mabey’s Nature Cure, a candid account of his recovery from depression, and how attending to the more-than-human world was part of that process. This book has stayed with me.

He writes, “It seems to be a basic human reaction, the first step in beginning a relationship: ‘What’s your name?”

For Mabey, knowing a name is the first step in a potential friendship. A greeting. A gesture that opens the possibility for further relation.

He continues, “It seems to me that naming a plant, and for that matter any living thing, is a gesture of respect towards its individuality, its distinction from the generalised green blur. It is, in a way, exactly a gesture: as natural and clarifying as pointing.”

Knowing a name, as Mabey suggests, opens the way perhaps towards some kind of intimacy.

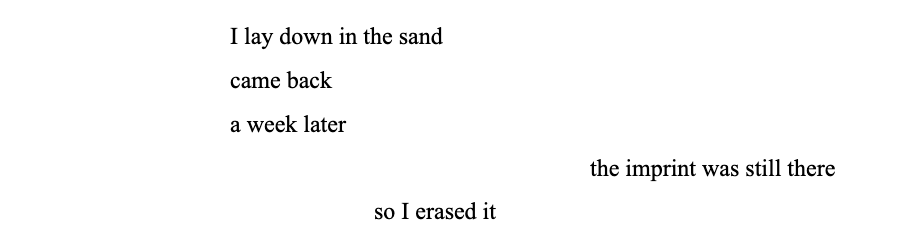

For me, saying a name creates a shift in focus.

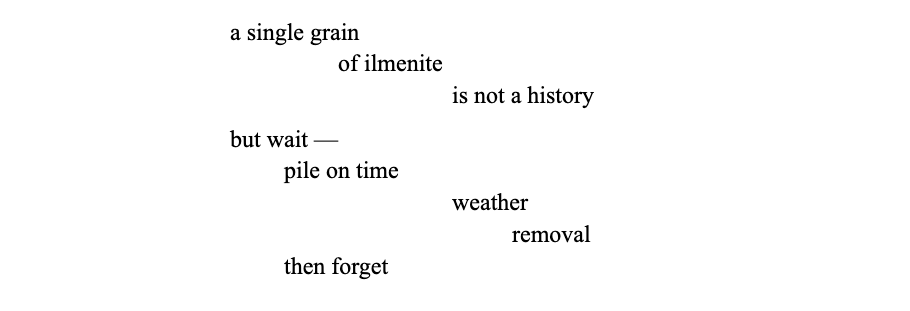

But names can be elusive, multitudinous, opaque.

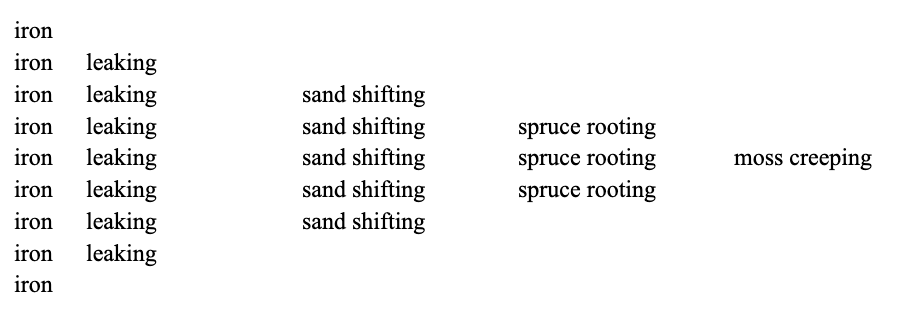

Naming, while intimate, also carries a history.

Human drives to classify and categorise have not been neutral. The Linnaean system that orders the living world into genus and species was born alongside projects of empire, extraction, enclosure. Naming as a means of possession. A grid laid over the earth.

In this history, to name was not only to know, but to claim. To fix a being’s place – and in doing so, make it available: to study, to harvest, to control. As Banu Subramamiam warns, “While the Linnaean system might seem simple in its binomial formulation, it was anything but. Its imagination and structures were fuelled by powerful ideas about colonialisms, race, gender, sexuality, and nation.”

Still, despite this weight, there remains something about the simple, faltering act of greeting – ‘Hello oak’ – that feels like a movement in another direction. An offering of attention without expectation, aware of nomenclature’s non-innocence.

Perhaps instead, my greeting should become a rendition.

Hello thick, ridged lichen-covered trunk with branches large and twisting outward and upward. Hello lobbed leaves, tarnished and folded by winter, still bronzing the soil beneath my feet.