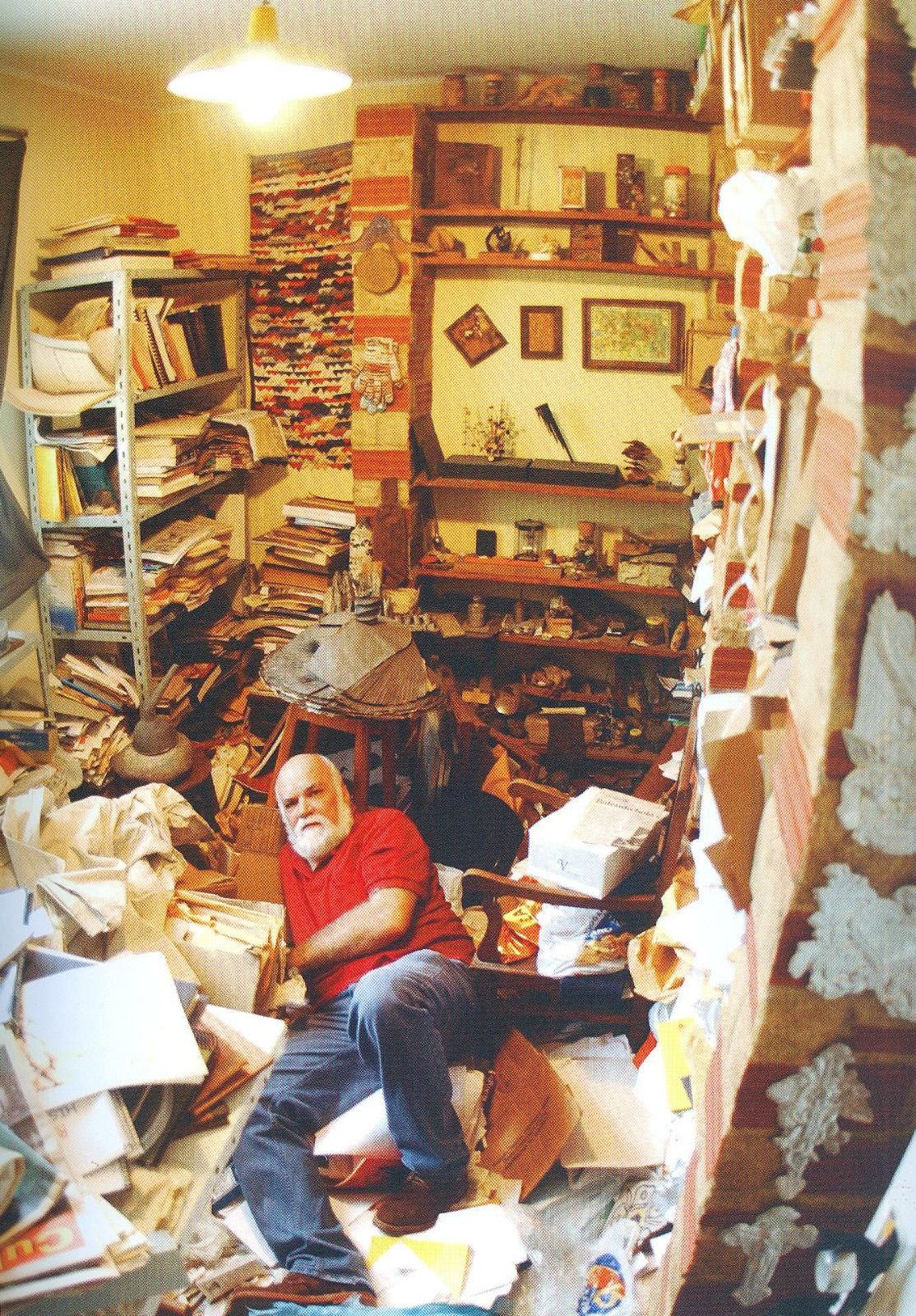

Handling artists’ books in a living archive like Bruscky’s in Recife, or taking them home from Sølvberget in Stavanger, are radically different experiences, yet linked by the same underground current, one as deep and persistent as the oceanic circulation connecting the two ports from the beginning of this text. Just as the waters that descend in the North Atlantic, in the landscapes that shaped Alexander Kielland, resurface transformed in the south, artists’ books also realize themselves through movement: they come alive as they travel between hands, homes, cities, and histories. They are bodies that demand proximity. They only fully exist when touched, leafed through, breathed. Between Recife and Stavanger, between the archive-studio and the public library, I now recognize a gesture common to both: the refusal of enclosure, the defense of knowledge that circulates, brushes, alters; the conviction that art is not meant to be merely contemplated from afar, but lived. The artists’ book, in this sense, functions like a small tide, a call to intimacy and a challenge to the boundaries between public and private, archive and home, museum and street. And perhaps that is why the phrase by Kielland, which lends its name to this residency, echoes here as well: it applies to the Norwegian writer, to Bruscky, and now to this author, moved by books that demand touch, circulation, and worlds in perpetual motion.

My fingers are also itching to move the world.