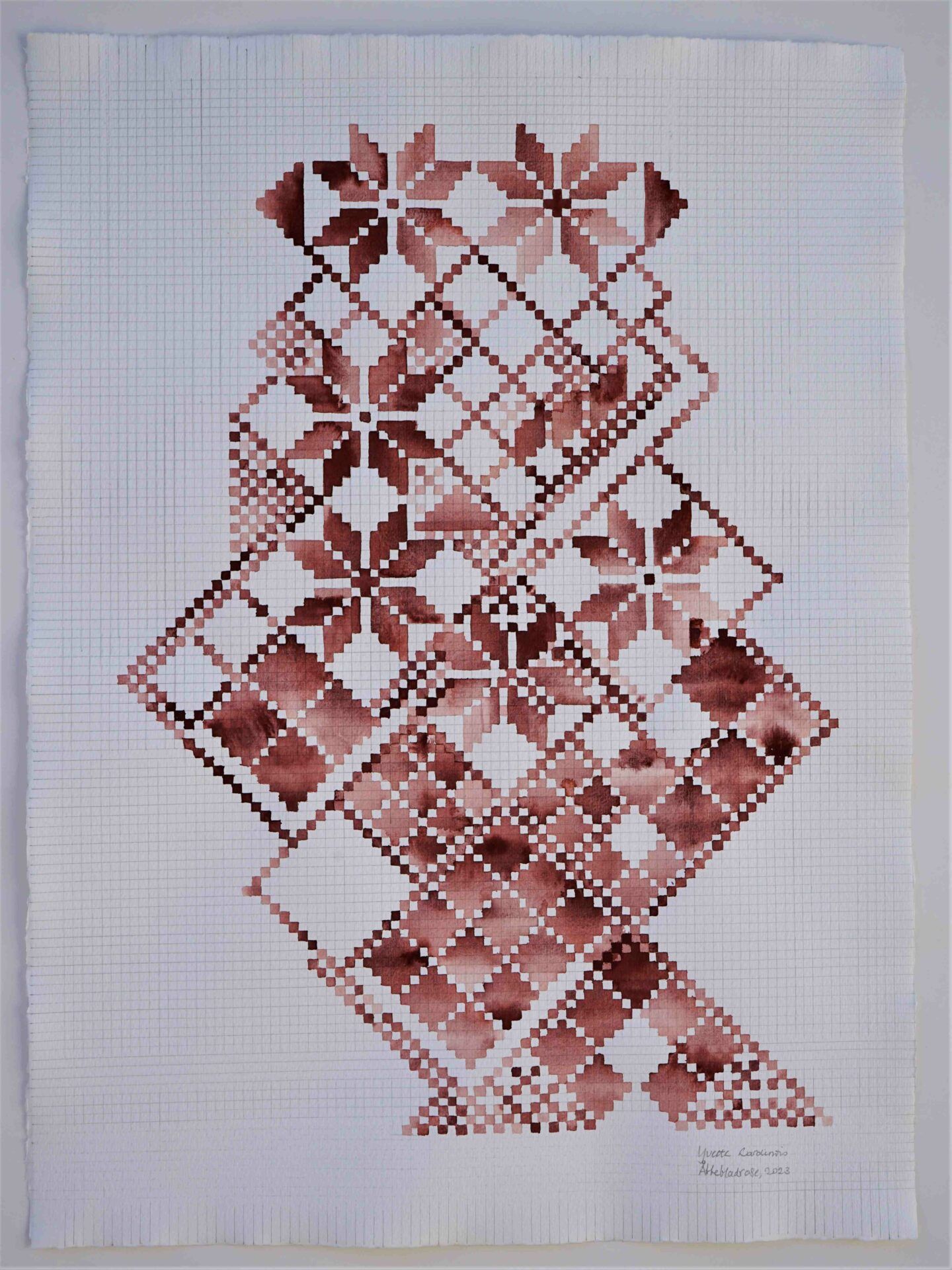

I came to Norway first to visit, about 20 years ago, and then to live with my now-husband Frank Åsnes, who is also an artist. Every time I arrived at Sola airport, I saw the åttebladrose pattern. At first, I associated it with my own feelings of love. Then I started reading about it. The åttebladrose is a very important cultural symbol. There was a priest in Norway, Eilert Sundt, who did a social survey on people around 1860. During that time, he saw that the women did such incredible textile works that were never shown outside of their own families. He was editor of the journal Folkevennen. He actively encouraged participation in exhibitions of Norwegian crafts so that women could compare their work to others’ and to show the outside world the excellent quality of their work.

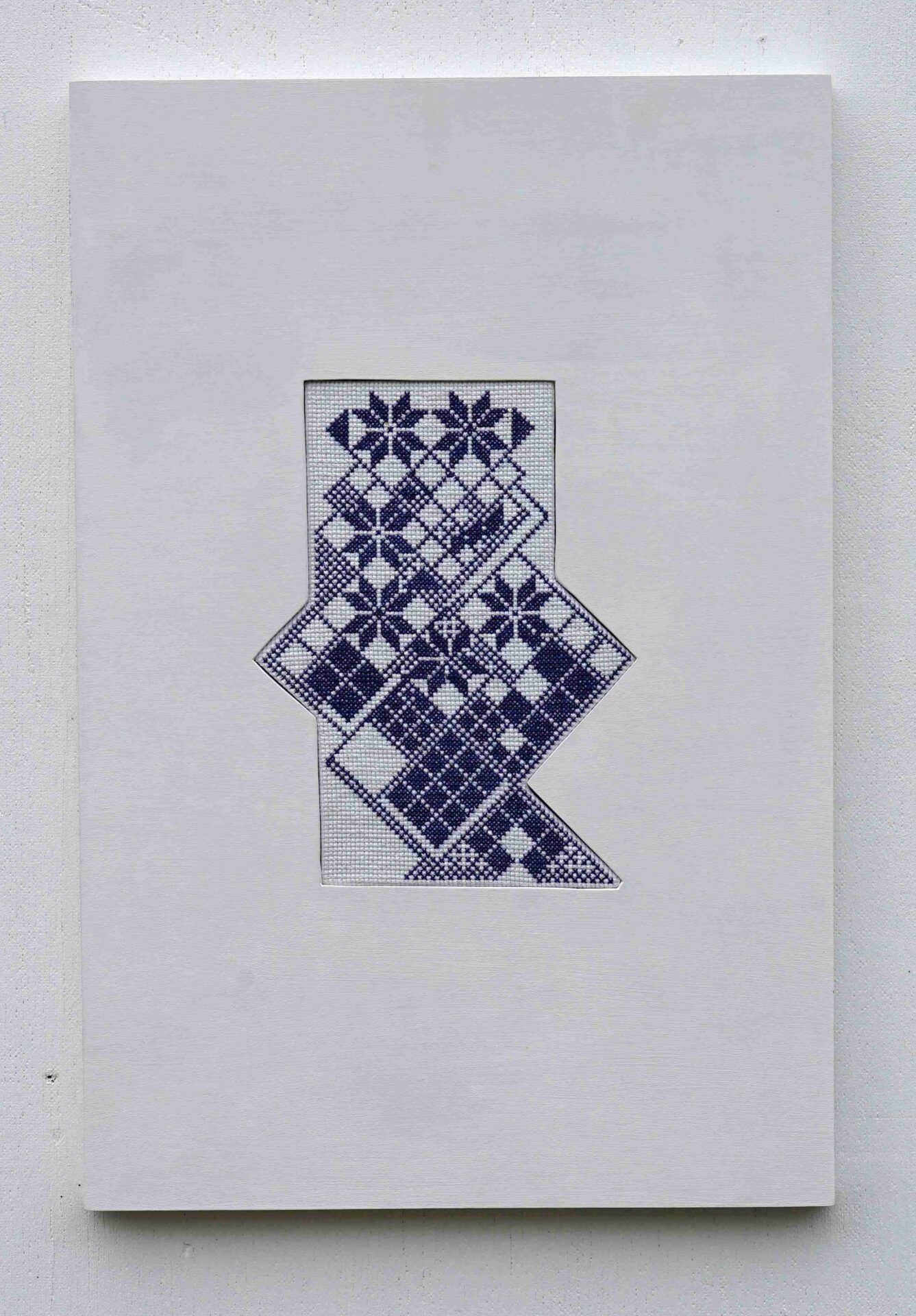

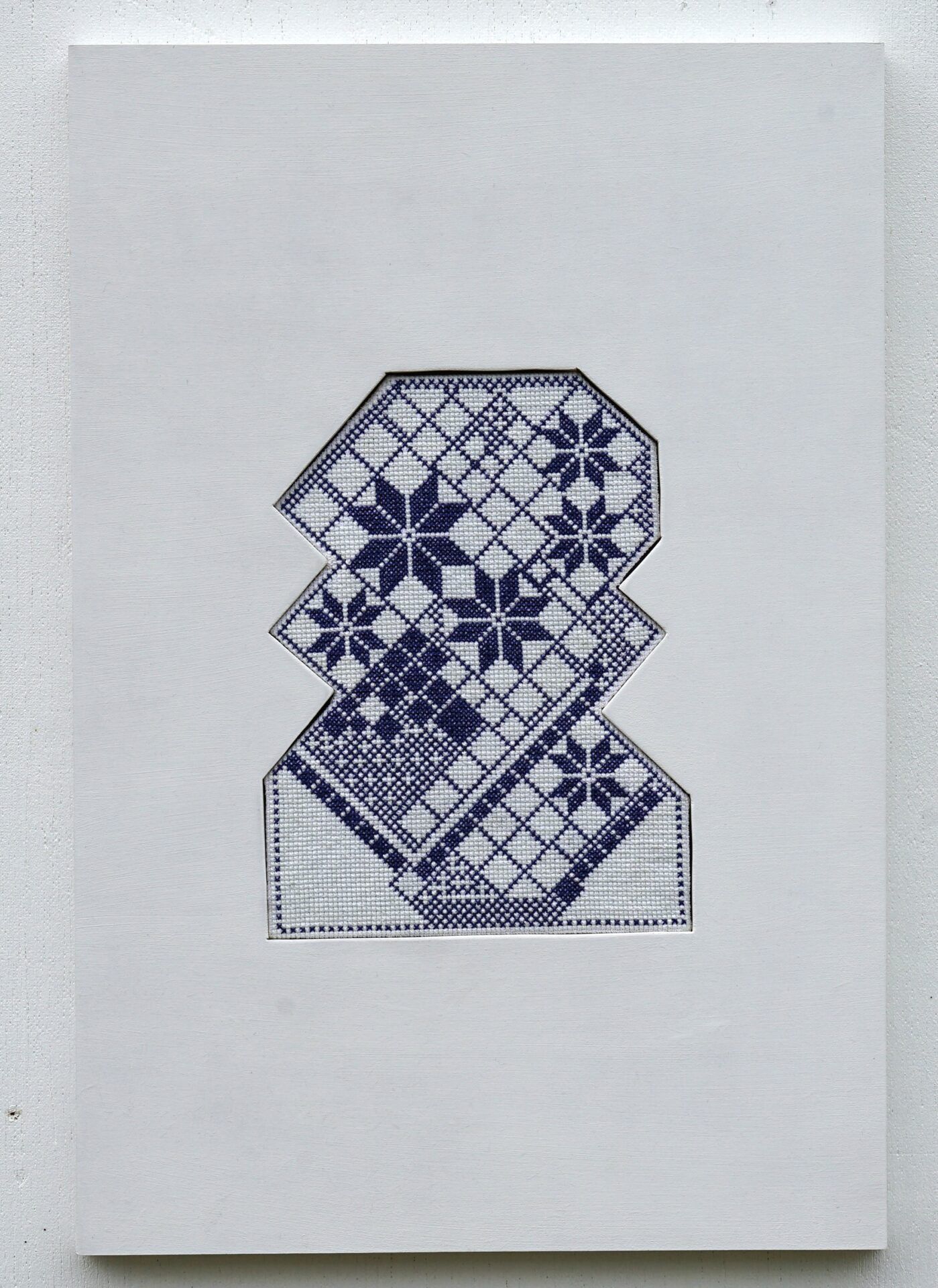

The åttebladrose is a symbol of being together and is connected to the entire national bunad tradition. In the beginning when I came here, I didn’t understand why people put it on. Slowly it is becoming clear – the way clothes and traditions are passed down and recycled. It is something you can have your whole life. You don’t have to go to a store and buy a new thing every time.

When I came to Norway, I no longer had a platform for my art. Frank was invited to make a sculpture for the sculpture park in Ålvik. It’s a very, very small town that completely revolves around a metal factory. And they have an old office that is now an artist house with a spectacular view on the Hardanger fjord. Then suddenly I had a studio again for a whole month while Frank worked next door. But I had no idea what to do. I decided to go for a walk to the library, which was only open 2 days a week. I went every day it was open for the whole month. I encountered books on traditional costumes in Norway but also all over the world.

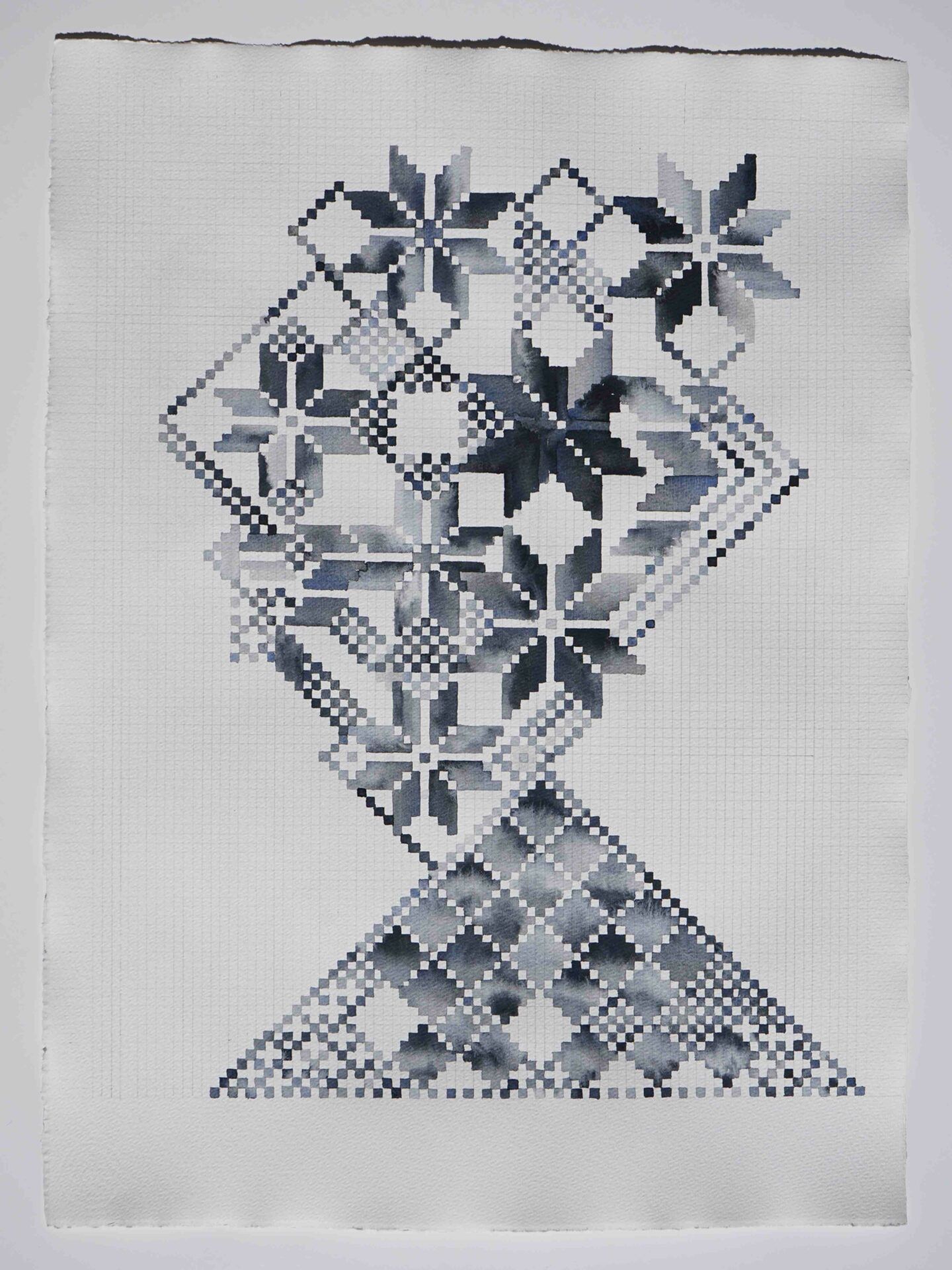

The beauty of an artist residency is to confront oneself. What do I want to do? In the studio, there was a big architect’s table with L rulers. I just put paper on it and started drawing grids. And then I said, okay, let’s fill them in. From that point, it went very quickly. I made a long accordion book and a small exhibition, but you can’t do much in a month.