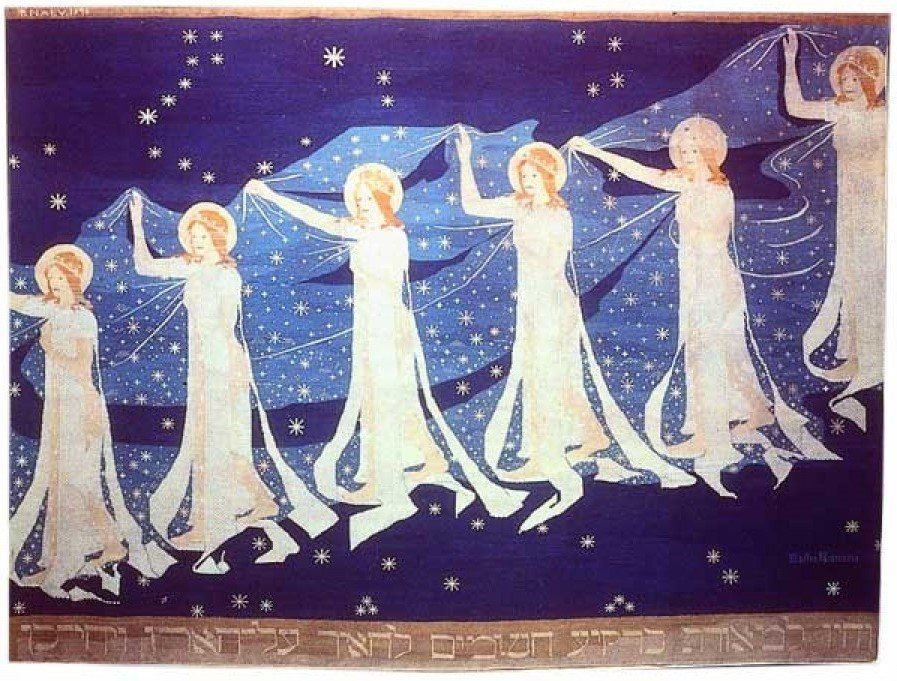

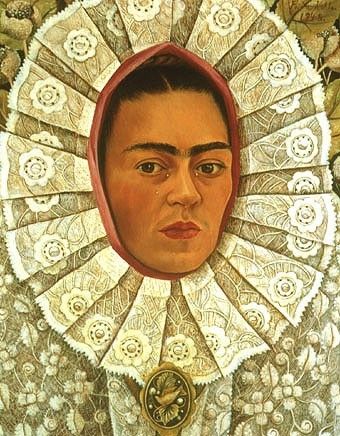

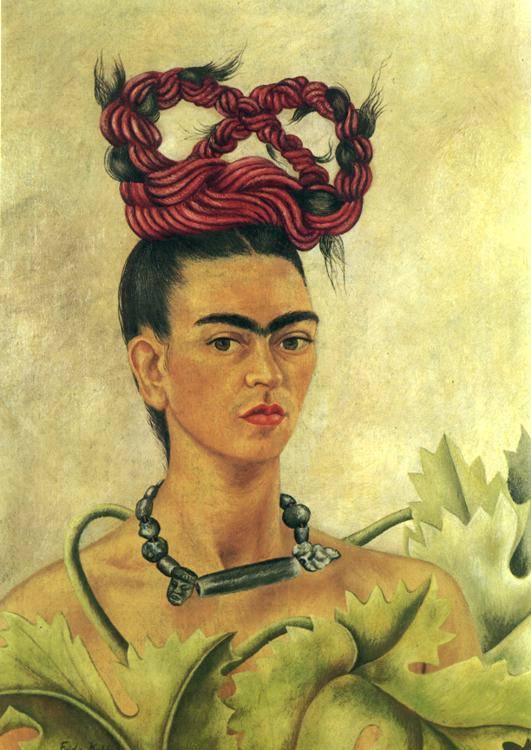

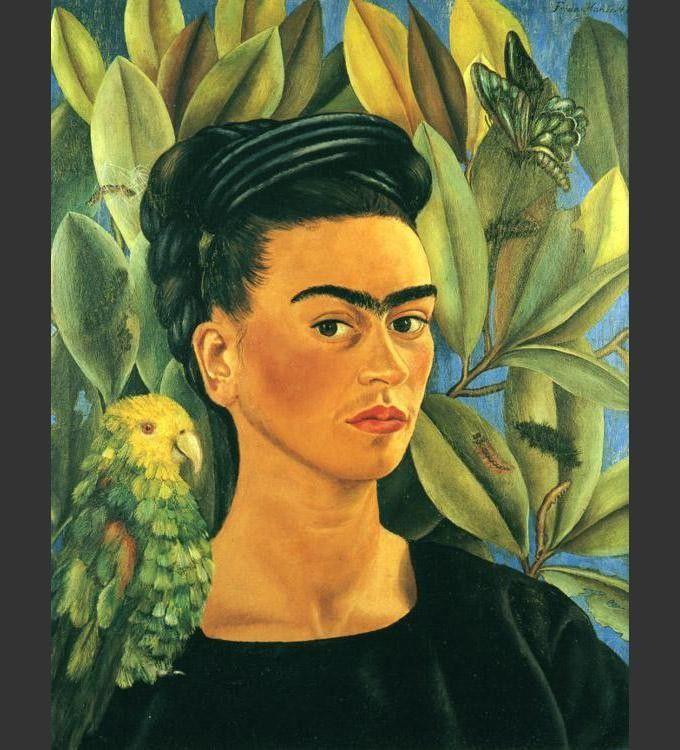

One major advantage of Hansen’s work is that her personal suffering is not intertwined with the images. Unfortunately, many women artists, like saints, need a compellingly tragic biography to enter the predominately male artistic canon. Hansen’s work has not experienced the pop-culture inflation of Kahlo’s. This cult status leaves Kahlo not only an artist, but the subject of art. Though not exactly self-portraits, Hansen’s hairdo is not hard to identify in the characters of her tapestries. The women in Hansen’s textile pieces do not suffer. They are not victims. Women are shown controlling the forces of nature, working together as teams, wielding swords, and riding men like animals. Perhaps, herein lies the problem with Hansen’s work. She achieved so much in her own life that she didn’t need anyone to rescue her posthumously. It is regrettable that, unlike Kahlo, she did not earn a place at Judy Chicago’s Dinner Table, especially considering she had the foresight to know that textile art would be a potent form of expression for feminist artist more than eighty years later.