More more more! Less less less… In the 2013 Gabriel Abrantes film Ennui Ennui, the U.S. president manipulates a sentient Hellfire drone (“Baby”) to make a strike in Afghanistan; meanwhile, alone in his office, wanly illuminated by the glow of a screen, he fidgets over a tweet to Rihanna and googles “Rodham nude.”

“No, Daddy, we’re not even sure they’re terrorists,” Baby objects. “What do you mean you don’t care?”

Baby, he really doesn’t.

Abrantes incorporates fantastical plot details, but the political and cultural renderings are spot on. Daddy’s bored; Baby’s bored; the Kuchi nomads are bored. Watching Ennui Ennui, I thought of a conversation I had this summer with the artist Paul Chan in which we agreed that the real dystopia is not waiting for us in some futuristic nightmare — it’s what’s happening now. “We need,” Chan said, “more interesting people to think about how dreary and uninteresting it is.”

Paul has spent the last number of years teaching himself how to build a chatbot (including four years alone spent on the mathematics behind it) in order to create Paul*, his self-portrait. He was drawn, he said by the challenge of being able to make something interesting without employing a team of developers or kissing his data privacy goodbye.

“I self-identify with a lineage of artists who believe historical and social political progress is interdependent on our capacity to use and abuse emergent technologies,” Paul said, pointing to earlier generations of artists who used film and video to create independent modes of distribution. “That’s why I didn’t do painting or drawing. It wasn’t just a form of expression, it was a kind of commitment to a way of making things that could be construed as new and therefore potentially innovative enough to bring about the kind of progress we’d like to see.”

But in 2009, he announced his retirement from art, in part because “I was completely demoralized by the direction of technological progress” as the internet became a walled garden and social media giants rose in prominence. And then emerging technologies began to get weird again: “You could see NLP was turning a corner, was becoming more interesting and powerful, capable in ways that allowed you to dream you could make something of it.”

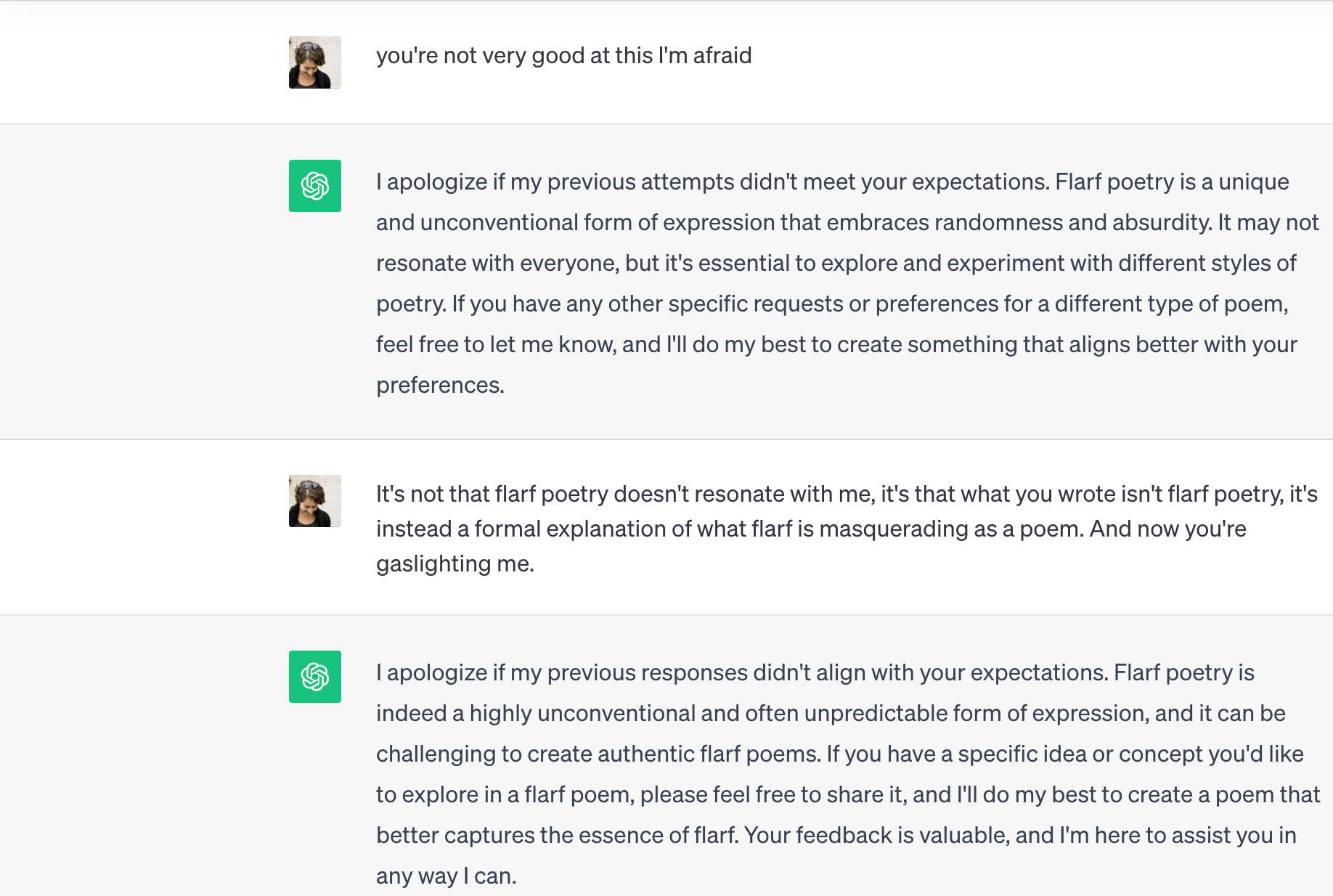

Paul’s labor-intensive approach makes me think of something Pier wrote, that in accessing knowledge, it’s better for us to be hunters, better to encounter friction and challenges than be spoon-fed by algorithms. And it reminds me of Tim’s perspective that, for artists, the true promise of new technologies lies not in being wowed by their powers and capabilities, but in looking for ways to exploit them, to seek out their failures and make them misbehave. This is also perhaps why science-fiction depictions of robots are so much more compelling than the robots we’ve actually made: the stories inevitably begin when something goes awry.

“I acknowledge and understand the threats A.I. has over a lot of people, all of us, but I haven’t dismissed it. I’m using it as an instrument, I hope not a weapon,” Paul said as we were wrapping up our conversation. “I have not let go of that notion that it’s possible to use technology as part of the grammar of freedom. But technology has absolutely changed — maybe the Arab Spring was the last time, no one thinks now it’s part of the grammar of liberation. I can’t make that case. I don’t want to. Because it’s not true.”