Function

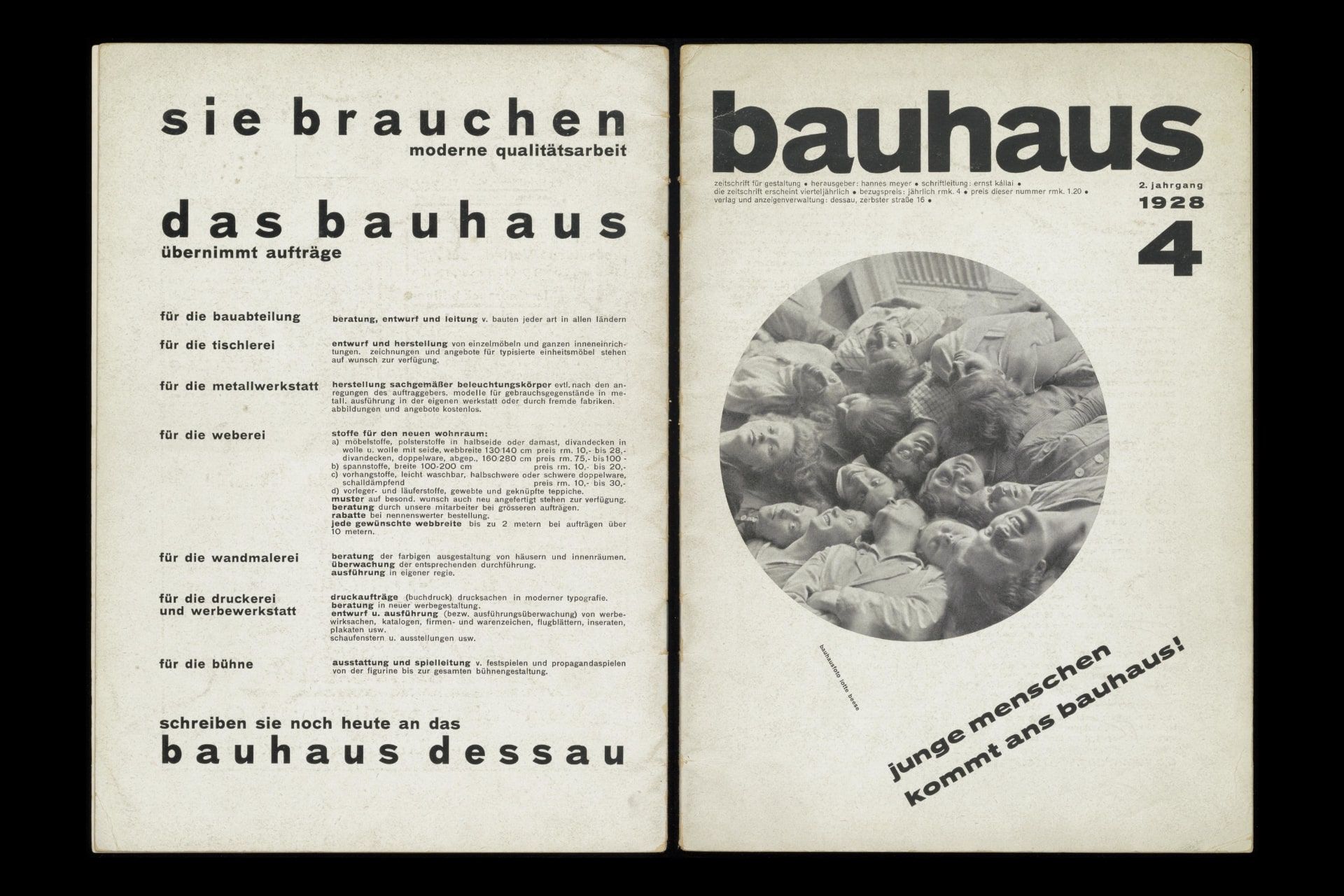

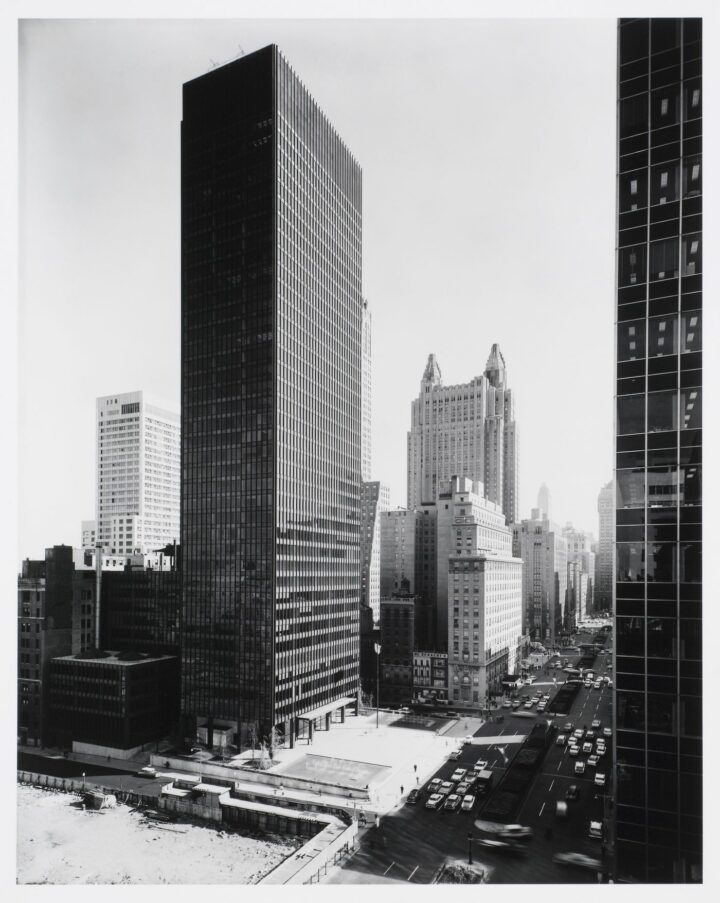

I encountered the echoes of the Bauhaus both in my education as an interior architect and the two years I spent working in an architecture office in Sydney. The office was established in 1949 by an Austrian architect who, after studying under Gropius at Harvard University, Josef Albers at the Black Mountain College, and working with Marcel Breuer, Alvar Aalto and Oscar Niemeyer, arrived in Australia a fervent disciple of modernism. He introduced Bauhaus principles to the Australian architectural landscape, altering the skyline of Sydney with some of its first highrise buildings.

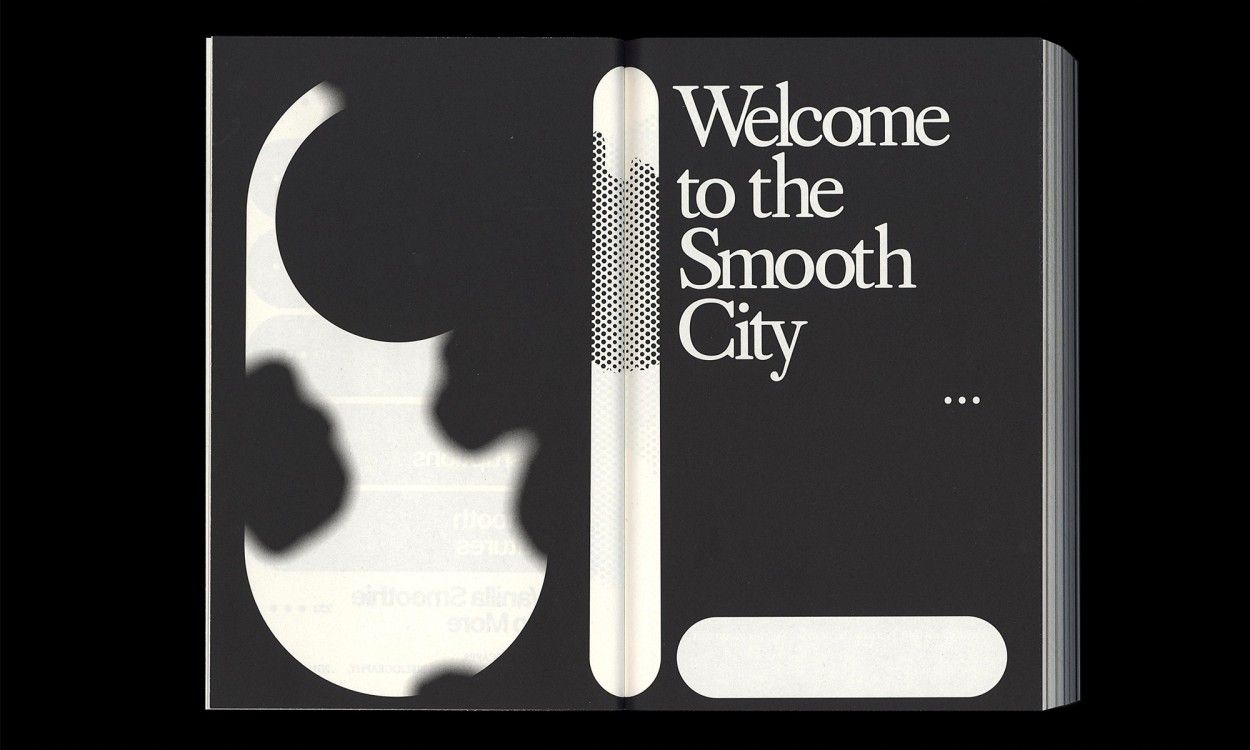

70 years later and 13 years after his death, I sat amongst this legacy, swinging side to side in a black leather and aluminium Eames office chair surrounded by off-form concrete and floor to ceiling glass windows. My boss, his successor, was kind and knowledgeable and taught me the principles integral to Modern architecture. I learnt that the smallest detail was as important as the overarching structure, and each should remain true to the design concept as a whole (a gesamtkunstwerk). When specifying finishes, the rule was that if the vertical surfaces, such as the walls, were light (travertine), then the horizontal surfaces, such as the floor, should be dark (black granite). Form always follows function, each element reduced to its purest form, and it is in this purity that beauty is found.