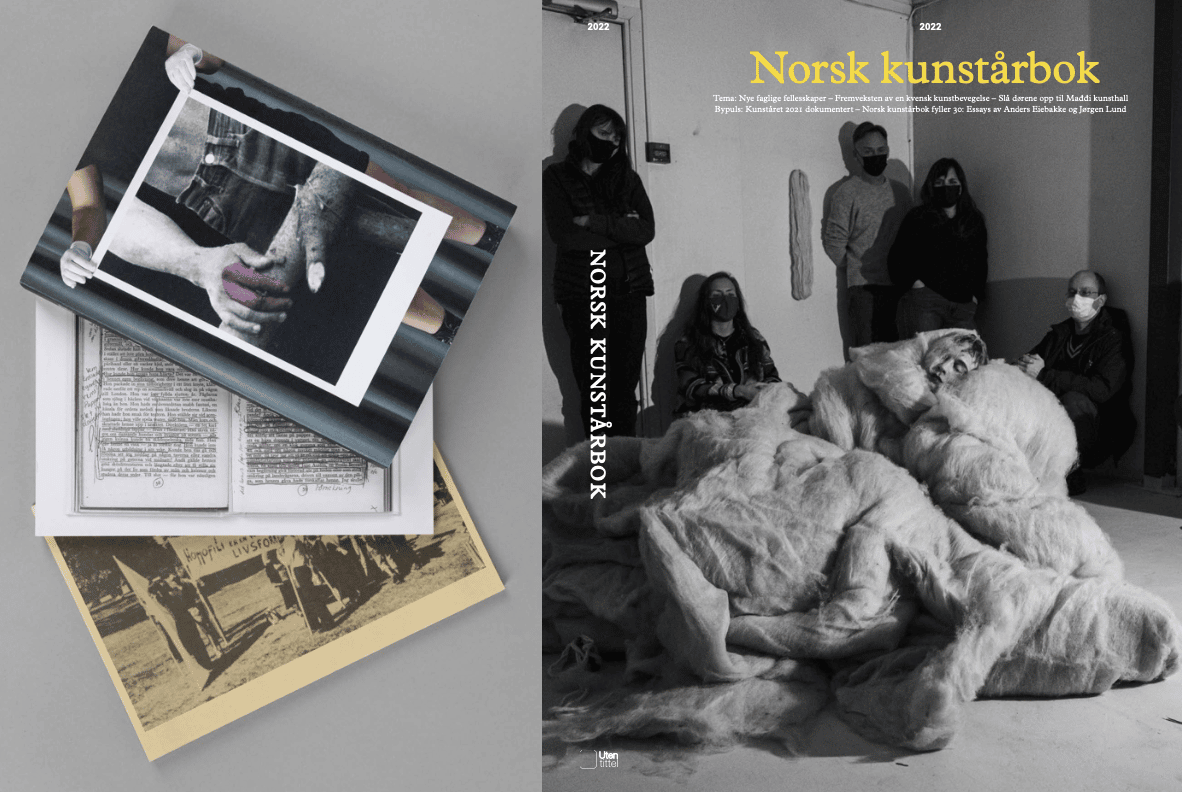

I find that things have grown quite organically over the years, and this is also a method I have great faith in. That's why I haven't applied for many jobs in my lifetime, even though the pay has been – and still is – the same as a minimum wage job. Community, friendship, creativity and joy must be at the center of what I do. I want to understand work as a life practice, and it is something I have prioritized over other things in life, like establishing a family for example. This can quickly become a long story, but I came to Bergen in 1999 to attend the writing academy Skrivekunstakademiet. I met the current editor of the magazine Vagant, Audun Lindholm, the following year while attending Forfatterstudiet (a creative writing school) at Høgskolen I Telemark in Bø and became part of his various indie literary activities. A that point it became clear that I was going to stay in Norway for a longer period of time. We had some fruitful years in the early 2000s where we knitted together a foundation for an art-and-life practice in a very creative and generous environment. As a result of some of these activities, I was invited to review literature for the Norwegian newspaper Klassekampen in 2003. I was referred to as a critic after that, and that was it. I took it very seriously! I pursued a Master's in Literary Studies at the University in Bergen with a strong interdisciplinary approach, and I was already starting to cross over into art history and mix things together with a focus on historical avant-garde movements. There was an art critic drought in Bergen and in 2009 Jonas Ekeberg and Mariann Enge invited me to write reviews for Kunstkritikk.no. Someone then called me an art critic and I once again took this label very seriously. Curiosity is what steers my ship, not the urge to make a reputation for myself in the eyes of others. My value as a writer and editor lies in my unfolding of ideas, and this only happens if there are things I wonder about. I have to mention my elderly engineer father who turns 80 in December. Without getting too sentimental, I guess I got my curiosity from him. He was always teaching me about the lives of other creatures and how things are built, whether furniture or bridges. I became involved with The Norwegian Art Yearbook in 2011 when Ketil Nergaard and Marie Nerland invited me to contribute. In 2019 I saw an open call for the editorial position and applied. I then went to Oslo for an interview, and was invited to start immediately afterwards. The book publisher PAX then announced that they no longer wished to continue the collaboration with The Norwegian Art Yearbook. It was an ammicable split, but then came Covid-19. That was a crisis of epic proportions, but I believe and hope that things are turning around. We are now very happy to be working with the Oslo-based publisher Uten Tittel.